As far as

economic, social, political and cultural matters are concerned, the majority of

German immigrants and their descendants have not only been fully integrated

into the American mainstream, in many respects they have even co-created it.

But the anti-melting pot vision of a separate German-style "model

state" within the Union was occasionally discussed until about 1850.

Travel-guide author Franz Löher, writing in 1847, describes the dream of a

German state that was to be situated somewhere between the Missouri River and

the Great Lakes:

As far as

economic, social, political and cultural matters are concerned, the majority of

German immigrants and their descendants have not only been fully integrated

into the American mainstream, in many respects they have even co-created it.

But the anti-melting pot vision of a separate German-style "model

state" within the Union was occasionally discussed until about 1850.

Travel-guide author Franz Löher, writing in 1847, describes the dream of a

German state that was to be situated somewhere between the Missouri River and

the Great Lakes:

They will become Americans, good republicans and good businessmen. They will mix with the non-Germans and will intermarry and will assume many of their manners. But the general tenor will remain German through and through. Our people will be able to produce wine on the riverbanks and drink it, accompanied by cheerful songs and dances. They will be able to have German schools and universities, German literature and art, German science and philosophy, German regiments, courts and state assemblies, in short, they will be able to build a German state in which their language will be the official language, just as English is now, and in which the German way of life will live, thrive and predominate exactly as the English way does everywhere now [Franz Löher, Geschichte und Zustände, 502].

Löher drew a lot of criticism from German-Americans who were afraid that his vision would attract Nativist attacks. Those very German refugees who had discovered political freedom in America were the ones most opposed to ethnic separatism. In 1848, Johann Bernard Stallo, a Latin teacher and lawyer who had immigrated ten years earlier, described more realistically the ambivalent feelings of those Germans who were in the process of adapting to the New World:

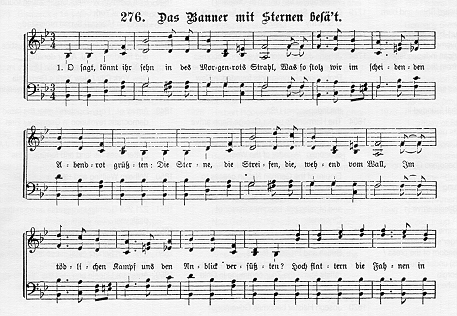

Being German-American is a very personal thing. We want and we find external independence here, a free middle-class way of life, uninhibited progress in industrial development, in short, political freedom. To this extent we are completely American. We build our houses the way Americans do, but inside there is a German hearth that glows. We wear an American hat, but under its brim German eyes peer forth from a German face. We love our wives with German fidelity. . . We live according to what is customary in America, but we hold dear our German customs and traditions. We speak English, but we think and feel in German. Our reason speaks with the words of an Anglo-American, but our hearts understand only our mother tongue. While our eyes are fixed on an American horizon, in our souls the dear old German sky arches upward. Our entire emotional lives are, in a word, German, and anything that would satisfy our inner longing must appear in German attire [Cincinnati Volksfreund, Nov. 13, 1 848].

In a similar vein, shortly before the Civil War an article in the Atlantis magazine saw nothing wrong with the notion of becoming American politically while remaining, for the most part, culturally German. An intellectual Forty-eighter who addressed this question in 1857 also used the word Schmelztiegel ("melting pot") for the first time as a metaphor of assimilation:

There has been so much talk about the fact that in this "melting pot" of the American nation the German nationality would be drowned, that "the German," as the technical term runs, would have to "Americanize." However, we believe that the German does not have to discard his social qualities and customs any more than he needs to deny his intellectual accomplishments, and that he is already sufficiently Americanized once he has acquired ideas about the self-government of a republic. This set of political ideas is the only belt strap that binds together the various population strands of the New World. Anyone who subscribes to this concept is worthy of American citizenship. Hence our Americanization requires nothing else but for us to adopt the ideas of democracy about human rights and the sovereignty of the people in social and political life. It is in this respect very significant that, to become a citizen, one has to fulfill no other conditions than to renounce allegiance to one's former sovereign. You do not have to chew tobacco or go bankrupt, neither speculate in lots, nor be a temperance advocate, and you do not have to run to church, nor capture Black men who are run-away slaves from the South. What Americanizes us completely is simply the decision, the firm conviction, and the capacity to be a free man [anon., Atlantis, Jan. 1857, 4-6].

The individual's efforts at economic security and social recognition were

actually strengthened by the rivalry of ethnic groups. Always postulated as the

long-range goal of all immigrant groups was "equality" with

"Yankeedom." But the driving force on the roadway to this goal was

more accurately: competition with the other immigrants. Feelings of self-worth

for many German immigrants, especially before 1830, may have been somewhat

unstable. Along these lines, the German-American historian Ernest Bruncken

commented in 1902:

Not even a half century has lapsed since the days when matters were not much better for the German than for the Chinaman. Whereas the Chinese at least belonged to a large nation, the Germans were members of 30 to 40 spittoon-sized principalities in Europe. As if from a spittoon-based existence, they came across, packed in like herrings, only to be sold for a time as redemptioners into slavery. Not a single voice was ever raised against this practice! The German immigrants were nothing more than white Negroes. That was the situation until the 1830s. Only with the arrival of men like Gustav Körner did matters gradually improve. This new German element proved that Germany had more to offer than human "work horses," that she also had intelligent people [Hense-Jensen / Bruncken, Wisconsins Deutsch-Amerikaner (1902), II, 131].

Complete and total integration of the Germans required many decades.

Baltimore, for instance, had long enjoyed the benefits of numerous and

successful German-American businesses. Nevertheless, writing as late as 1905,

the editor of a German-language anniversary book entitled Das Neue

Baltimore, in which special emphasis was placed on German-Americans in the

business life of the community, still considered it necessary to remind

Anglo-Americans that it was not in their best interest to look down their noses

at German immigrants. For without their often-mocked industry and without their

hard work, he said, Baltimore would never have become what it is today. The

once recognizably German sections in America's big cities have pretty much

disappeared since the 1920s. This is in contrast to the greater longevity of

Italian, Polish and Chinese sections. In the 19th century, however, there were

unmistakably German residential and business centers in many of the large

cities. In New York there was "Kleindeutschland," in Chicago it was

the North Side, in Cincinnati "Over the Rhine," and in New Orleans

"Little Saxony." Similar German colonies existed in Buffalo,

Milwaukee, St. Louis, Indianapolis, and in smaller cities as well. Over 37% of

German immigrants in 1860 lived in cities with more than 15,000 inhabitants;

and by 1890 this figure had risen to 40% and to over 54% by 1920. This tendency

to become urban was much greater for Germans than for the American population

as a whole. Even though the larger cities were frequently considered as mere

transition stations for 19th century Germans on their way to the rural areas or

small towns, many did remain in the place where they first settled.

The following impression of the German presence in Milwaukee during the 1850s was offered by a Danish traveler: "German houses, German inscriptions over the doors or on signs, and German faces everywhere. . .. Many Germans who live here learn no English and they seldom exit from their own German section of the city." But even in their highest concentrations, the Germans never dominated a single city exclusively. They always had to make accommodations with other immigrant groups, especially the Irish.

Even before the Colonies won their independence from the British crown, the inhabitants of Germantown and the Germans and their offspring living elsewhere in Pennsylvania frequently changed their names by Anglicizing them; and they readily used English in business dealings. Another sign of their assimilation well before 1800 was the increasing number of marriages with partners from outside their group. In church life, a relaxation of ethnic exclusiveness also became obvious. Around 1800 already, many Lutheran and Reformed pastors complained of the need to add English-language services and to hire younger English-speaking pastors to meet the demands of younger members of their congregations.

Only those denominations with a religious order-like membership in their

virtually closed sectarian communities, such as the Hutterites, the Harmonists,

the Amish and certain Old Order Mennonites, held fast to their German worship

language and their everyday German dialects. This residential and linguistic

isolation from their English-speaking environment made it almost impossible for

their children to leave their hallowed faith.

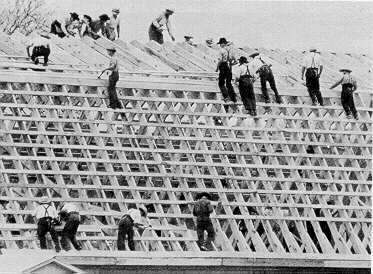

Outside their hallowed religious grounds, Germans grasped at many an opportunity to assimilate. The Civil War, for example, offered all European immigrants the chance to earn for themselves a place in the new national community by means of voluntary service in the military. A German-American speaker at a festival gathering in 1882 reminded his audience of Lincoln's first call to arms, which was answered as much by adoptive citizens as by Anglo-Americans: "In this great moment in the history of the United States there were no Irish, no Germans, no Scandinavians, no aliens, but only Americans. . . . All fought like brothers, shoulder to shoulder, for one holy purpose -- the preservation of the Union -- and, with it, for the salvation of the last great bastion of freedom and for all the suppressed and the underprivileged of all nations" [See Hense-Jensen / Bruncken (1902), II, 117].

Because of the strong and active participation of German-Americans in the Civil War on the side of the North, the political socialization of the entire German ethnic group accelerated, which in turn caused a rapidly increasing number of German-Americans, including even politicians who had been born in Germany, to get elected or chosen for appointment to public offices, ranging all the way from local school boards to state legislatures, even the U.S. Congress and the presidential cabinet.

Linguistic and cultural integration for the vast majority of German-Americans was motivated more than anything by their determination to improve their standard of living. Not very many immigrants experienced the fortunate fate of youth-book heroes as popularized by Horatio Alger during the 1870s and '80s, namely, that initiative and honesty would enable one to rise "from dishwasher to millionaire" -- a catch phrase also very popular throughout the German-speaking countries. Numerous immigrants and their children achieved economic success, which in turn made them very proud of their environment and the social and political community in whose surroundings they had experienced their achievements. Personal success and the collective goals of an entire city or region often fused the self-worth feelings and identities of the immigrants, not with other immigrants, but with the trans-ethnic "American" community which had made "progress and equal opportunity" a political creed embraced by all hardworking and talented immigrants. Many of the successful German-Americans, like other immigrants, had little reason to identify with their past and the ethnic community they had left behind when their future belonged so obviously to the thriving supra-ethnic corporate body they had joined. Upward social and economic mobility tended to weaken ethnic ties.

Writing in 1928, the American social critic and grandson of an immigrant, H.

L. Mencken, pointed out how swiftly the process of assimilation had been

absorbing the German-Americans, even before the First World War: "The

melting pot has swallowed up the German-Americans as no other group, not even

the Irish." Might one assume then, that the Germans permitted themselves

to be assimilated in model fashion -- that they gave up their ethnic identity

without a fuss? This was not quite the case. Making out of a German first a

"German-American" and then finally just an "American"

required much tolerance and openness, in particular on the part of the host

society.

The "ghettos" or the "colonies" of individual immigrant groups in certain sections of the big cities have long since been acknowledged by American immigration researchers as useful transition stages on the long and tedious path to integration into the English-speaking middle class. To illustrate the support which group settlement of immigrants affords, we can compare it with a "decompression chamber" which, as in a diver's case, eases the step-by-step ascent into the new society. This metaphor is meant to belittle neither the life-threatening living conditions in the New York tenement houses of the 1880s, nor the concentration of foreign children in the inner city schools of the 1990s. No doubt, the process of acceptance and integration of ethnic minorities will suffer setbacks in urban centers everywhere in the world. A functioning multicultural society does not come about without the best effort on the part of all concerned. However, the German-American experience can shed some light on the process and help strengthen our rationality in the face of doom prophets and nativistic hate mongers.