The degree to which Germans dispersed across the entire country and the

speed with which

their ethnic group was integrated into the English-speaking American

middle class could, of

course, not have been anticipated by their contemporaries. Like other

immigrant groups, the

Germans followed the natural instinct of forming neighborhoods with their

countrymen where

they felt at home far away from home. They preferred to head for a region

where they could still

acquire reasonably priced farm land in areas where German-language

churches and perhaps

German schools already existed. Thus, the path taken by an individual

often turned out to be but a

link in a growing chain that bound the Old Homeland to the new target

region. Scholars address

this as "chain migration" and cite, for example, the fact that many

Hannoverians, Oldenburgers,

and Braunschweigers traveled by way of Bremen and New Orleans to Ohio and

Missouri. Most of

the Mecklenburgers journeyed by way of Hamburg and New York and then by

railroad and ship

across the Great Lakes to Chicago and Milwaukee. This resulted in our

thinking of Milwaukee as

the "Mecklenburg capital" of the United States. Micro-studies show that

emigrants from the same

village tended to follow each other to neighboring townships and counties

in the New World

[Kamphoefner, The Westfalians, 77].

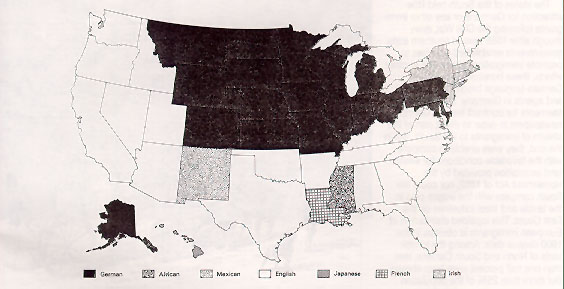

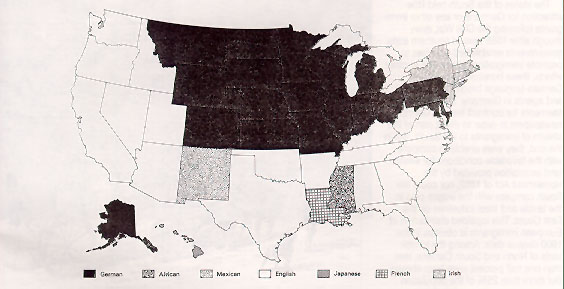

[National Origins of U.S. population by states with largest

concentrations, 1983. (Source: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1980 census Population. Supplementary Report PC 80-SI10:

ancestry of Population by State: 1980 (Washington, D.C.: Government

Printing Office,1983).]

The dream of establishing a German dominated belt, or perhaps an

exclusively German state

in the new Union, was never realized in spite of several attempts at

large-group occupancy, such

as the settlement of over 7,000 Germans by the Adelsverein of Mainz in

Texas during the 1840s.

As a rule, the choice of a destination by the newcomers was greatly

influenced by the time frame

of their arrival. That is, there were differing phases of colonization in

the West, as well as stages

of industrialization and urbanization in the East. In the course of the

19th century, the vast

majority of Germans settled in a quadrangle encompassing the states from

Ohio to Missouri on

the south quadrant, and from Michigan to North Dakota and down to

Nebraska on the north and

west quadrants. These territories were accessible on waterways from New

Orleans up the

Mississippi and the Ohio, or the Missouri, or from New York across the

Erie Canal and the Great

Lakes, and out to areas already connected by railroads. For craftsmen,

the booming cities of

Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Louisville, St. Louis and Chicago

offered job opportunities,

which could be said also for East Coast cities like New York,

Philadelphia and Baltimore.

The dream of establishing a German dominated belt, or perhaps an

exclusively German state

in the new Union, was never realized in spite of several attempts at

large-group occupancy, such

as the settlement of over 7,000 Germans by the Adelsverein of Mainz in

Texas during the 1840s.

As a rule, the choice of a destination by the newcomers was greatly

influenced by the time frame

of their arrival. That is, there were differing phases of colonization in

the West, as well as stages

of industrialization and urbanization in the East. In the course of the

19th century, the vast

majority of Germans settled in a quadrangle encompassing the states from

Ohio to Missouri on

the south quadrant, and from Michigan to North Dakota and down to

Nebraska on the north and

west quadrants. These territories were accessible on waterways from New

Orleans up the

Mississippi and the Ohio, or the Missouri, or from New York across the

Erie Canal and the Great

Lakes, and out to areas already connected by railroads. For craftsmen,

the booming cities of

Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Louisville, St. Louis and Chicago

offered job opportunities,

which could be said also for East Coast cities like New York,

Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Between 1850 and 1920, more than 30% of all German immigrants and their

children were living in the Mid-Atlantic states. During the same period,

the percentage for the

Midwest hovered between 35 and 39%. Just as inland migration within

Europe turned at times

into overseas emigration, so too in America the stream of immigrants

followed in part the

pathways of westward migrations, moving perhaps from Pennsylvania to Ohio

and Indiana, or

maybe on a route up the Hudson, westward by way of Albany and Buffalo and

thence across the Great Lakes to Cleveland and Detroit, Milwaukee and

Chicago. These

transportation patterns resulted in the principal German settlement

region -- both rural and

urban -- mentioned above. At least a third of Wisconsin's population in

1900 was either

German-born or had at least one parent who was born in Germany; in both

Minnesota and Illinois

it was more than a fifth of the population.

The states of the South held little attraction for Germans or any other immigrants following the Civil War, even though after 1865 several southern state governments established agencies to promote immigration. In addition to other efforts, these bureaus made use of German-language brochures, placards and agents in Germany. They put advertisements for contract labor in German newspapers in order to direct part of the stream of immigrants to the South. But in the end, they were unable to compete with the favorable conditions for western land acquisition provided by the Homestead Act of 1862, nor could the South compete with the wages paid in the textile and steel industries on the East Coast. This lopsided distribution of European immigrants is obvious in the 1900 census data. Among the inhabitants of North and South Carolina, less than one half percent were born abroad. But more than 25% of the population had been born abroad in the states of New York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Montana and Minnesota; North Dakota outdistanced all others with 35.4% born abroad. The unequal distribution of the Germans across the nine major regions of the United States from the New England states to the Pacific can easily be observed in the following table.

| Table 4. Distribution of German-born, 1850-1960 (In percent) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | 1850 | 1860 | 1920 | 1960 |

| New England | 1.2 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 3.9 |

| Middle Atlantic | 36.0 | 30.0 | 30.1 | 38.5 |

| East North-Central | 39.1 | 39.8 | 35.1 | 25.3 |

| West North-Central | 9.0 | 16.6 | 17.4 | 7.1 |

| South Atlantic | 6.6 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 5.8 |

| East South-Central | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| West South-Central | 4.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.2 |

| Mountain | -.- | 0.8 | 2.0 | 2.9 |

| Pacific | 0.6 | 2.5 | 6.1 | 13.2 |

[Source: Cathleen Conzen, "Germans," (1980), 412.]