Another reason why German immigrants never formed a solid ethnic bloc

in the United States

was that they crossed the Atlantic with different interests and

expectations. Also, their financial

means varied from the large land owner, for example, who had sold his

home and farm in

Württemberg and had already commissioned someone to purchase land

for him in Wisconsin

before leaving, right down to the penniless farm hand who could not pay

passage for himself and

his family and thus had to mortgage his future.

To finance their passage, many of the penniless before 1820 became "indentured servants," also known as "redemptioners." The typical indentured service contract made out with the captain of a ship provided that the fare had to be paid together with an additional 12% premium no later than fourteen days after arrival. If a passenger was not able to wipe out the debt -- perhaps with help from a relative or a friend in America -- then the captain was at liberty to "sell" the passenger into a form of servitude, often together with his wife and children, for three to four years. Estimates suggest that half of all early German immigrants financed their passage in this manner. To be sure, only non-German harbors, in particular Rotterdam and Amsterdam, permitted this manner of passage. Shippers in Hamburg and Bremen demanded cash payment.

Really profiting from this kind of contract work were the employers

who in the year 1800

paid "bail" amounts of about $70 for a healthy adult in return for three

years of hard work. Under

normal circumstances the owner could realize a profit of between $500 and

$900 from his

purchase. A "serve," as these workers were known in German-American

conversation, worked

for about six cents per day while a "free" day laborer, who likewise

enjoyed complimentary meals

and lodging, earned between 50 cents and one dollar per day. A casual

observer of 1823 points

out the possibility for abuse:

The situation is unbelievably difficult for those people who did not pre-pay their own freight. They almost always fall into the hands of unscrupulous men. Usually only such a farmer would buy a serve [that's how the people are called who have to work to pay back their passage] who could not get any hired hands, for the simple reason that he did not treat them right. He exploits his serve miserably in order to earn back the passage costs in the shortest possible time. Once it has been earned back and the fellow leaves, nothing is lost. Often a serve is beaten like a slave [Johannes Schweizer, Reise nach Nordamerika. Leipzig: 1823,115].

Also comparable to slavery was the regulation that the indentured

servant could be assigned

to another master; family members often became separated from each other,

even forcing children

to be separated from their parents. It was not uncommon to read

advertisements in the

newspapers with descriptions of serves who had escaped, usually offering

a reward for their

recapture.

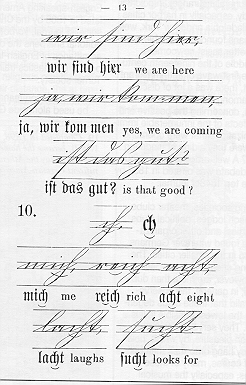

On the other hand, emigration advisers also pointed out the positive sides of indentured status. Those families who initially worked as indentured servants acclimated more rapidly to their surroundings. They picked up the language more readily, got acquainted with American farming methods, learned the techniques of craftsmen, as well as about commerce and the law. As a matter of fact, new arrivals were sometimes advised to volunteer for indentured service as a means to eventually increase their starting capital. Eventually, a federal law of 1855 forbidding contract labor immigration would have put an end to indentured service, had it not been abandoned for all practical purposes in the 1820s due to economic developments.

The dream of most German immigrants in the 18th and 19th centuries was

the debt-free

ownership of a farm. Taking up city residence initially often was a

strategy to build up savings of

$50 to $150. Around 1850 in Missouri this sum was sufficient for a down

payment on a farm of

about 40 acres, which was about the size needed to make a living. In

addition, the immigrant

needed about $500 to acquire implements, cattle and seed grains, as well

as food that would last

until the first harvest. The minimal chattel needed to be able to start a

family farm on the western

prairies around 1870 was a team of horses, a plow and other field

implements as well as seed

grain, which together cost about $1,200. That was more than the average

annual income of a

factory worker.

By comparison, German farmers were far more attached to their farms than others, succumbing less frequently to speculative fever. Instead, they tried to buy up land in their own vicinity for their siblings and children in order to be able to farm together for several generations. In 1868, a German farmer in Missouri described the opposite attitude, for which he had little sympathy:

There are people here who are forever moving around. They buy themselves a piece of land, live on it a while, work like a dog, and then, when they do not end up rich in a few short years, they curse the area, sell everything for a song, and move on to spots where they finish up worse off than when they left. Sometimes they return and would be delighted if only they could buy back their original land. In this way they frequently move five or six times before they finally come to their senses and admit that wealth does not fly into every mouth that opens [Kamphoefner, News, 168].

As a matter of fact, the persistency of Germans in certain regions of Wisconsin, the Dakotas, Minnesota, Illinois, Missouri, Indiana and Texas resulted in German islands that have lasted well into the 20tH century, at least in the sense of German conservative-rural, family-oriented values and memories.

If we categorize them by occupation, the largest group of German

immigrants in any given

period were those in the skilled crafts. Upon their arrival in Chicago in

1875, for example, one

third of the Germans were registered as skilled craftsmen, a quarter of

them as common laborers,

and another quarter as farmers. Both in urban and rural settings,

Germans held an equally high

profile as businessmen and shopkeepers, and in the final third of the

century also as skilled

laborers. Some fields of work were filled almost exclusively by Germans,

for example, brewers,

watchmakers, distillery workers and land surveyors. They supplied a large

proportion of the

bakers and butchers, cabinet makers and blacksmiths, tailors and flour

millers, stone masons and

tinners, cigar makers, shoe makers, typesetters and printers. Well paid

indeed were mechanics,

plumbers, and plasterers.

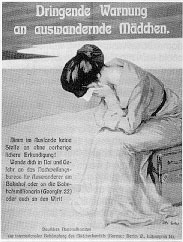

Especially in high demand in the category of unskilled workers, and continuing through all periods of immigration, were domestic servants -- young women who could earn more working in an English-speaking home than in a German-language household of their fellow countrymen. Potential emigrants from certain other occupational categories were well advised not to leave Germany, for they were not in demand. For example, an emigrant guidebook of 1859 admonishes caustically but certainly not erroneously, "a sloppy student would end up a fanatic Methodist preacher; a discarded lieutenant would end up splitting wood or boiling soap; a proud Baron would end up driving a team of oxen; a Catholic priest might end up with a wife and child, happily farming; but a clever stable hand is now in charge of one of the largest business places in St. Louis" [Friedrich Munch, Der Staat Missouri, 1859, quoted by Görisch (1990), 267]. Another guidebook in the 1890s warned that, "those who should under no circumstances even consider emigration include clerks, school teachers, writers, scholars, preachers, telegraph operators, civil servants, students and military officers, even if they have to continue working under the most unfavorable conditions in Germany. For this class of people there are no opportunities whatsoever in America" [Görisch (1990), 203].

Another pointer that frequently appears in emigration guides as well as in letters coming back from America is equally down to earth, namely the nearly unrestricted right to conduct business in America, which was unheard of in Germany. This economic freedom called for both geographical and occupational mobility. Thus in 1868 a successful farmer from Missouri reported to his parents in Germany that America offered some great advantages, "the greatest is that you can be more independent than there, that you can start something today, if you are not happy or satisfied you can start something else without making a stir. That is the main thing that makes America so dear to people, the freedom of movement, in many other things Germany is almost as good" [Kamphoefner, News, 164-5].

The family as an economic unit and as the cornerstone of the social

structure probably played

an important role for most Germans -- farmers, skilled workers, and

industrial laborers alike. Many

commentators have discussed family orientation as a highly significant

feature of the

German-Americans. The Germans practically swore allegiance to the value

of the family as the

core of a strong society. Outsiders, however, in comparing German and

Anglo-American family

patterns, have also commented on the domineering role played by the

German father and the

subservience of his wife and children.

German women were less frequently employed outside the home, but the

influence of their

work on the farm was all the greater. Wife-beaters, however, were

apparently found less in

Anglo-American families than in German families. The 1868 example of Carl

Wihl, a farmer in

Indiana, also shows that it was less tolerated in America: "He beat up

his wife for every little

thing," reported his neighbor writing to Germany, "and that's not done

here; here, a wife must be

treated like a wife and not like a scrub rag like I saw in Germany so

often, that a man can do what

he wants to with his wife. He who likes to beat his wife had better stay

in Germany, it doesn't

work here, or soon he'll not have a wife anymore, that's what happened to

Carl Wihl"

[Kamphoefner, News, 139].

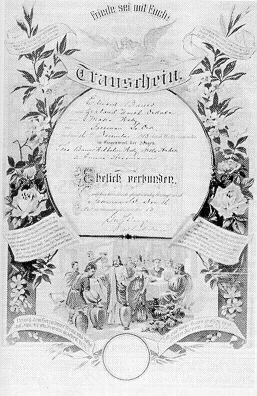

There is as yet no comprehensive statistical analysis concerning the

German-American's

choice of a mate . One

sample

that is perhaps not very

representative because it deals with the lives of successful business

people in Milwaukee, who

themselves or whose parents had immigrated from Germany, shows the

following results of mate

selection: From among the 16 who immigrated before 1882 and who averaged

25 years of age,

75% married a German woman. Only three married an American, three did not

get married. Of

the 32 children of German immigrants who were born in America around the

turn of the century

of German parents, or with one parent born in Germany, and who in 1920

were at the head of

their companies and married on the average at age 28, 66% married

"German" women but not

necessarily women who had been born in Germany. Only five of them married

Americans. Six

picked someone out of the melting pot and decided to marry non-Germans or

a non-American, for

that matter. Four never even took the plunge.

Studies on intermarriage

between Germans and

others on the American frontier include Hildegard Binder Johnson,

"Intermarriages Between

German Pioneers and Other Nationalities in Minnesota in 1860 and

1870,"American Journal of

Sociology, 51 (1946), 299-304, and Richard M. Bernard, The Melting

Pot and the Altar:

Marital Assimilation in Early Twentieth-Century Wisconsin

(Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1980).