The tendency of German immigrants to settle in close proximity to each

other encouraged the

continuation of familiar lifestyles. Significant problems of

assimilation and adjustment were more

easily solved when at least some behavioral patterns of everyday life

could be retained, such as, shopping at a German

baker or butcher, and enjoying a beer in a German tavern or beer garden.

Likewise, if a German worked together with

Yankees and other immigrants, he much preferred to spend his free time

with his

fellow countrymen. This resulted in enterprising German-language

organizations that

encompassed all aspects of life, extending from the singing society to

the gymnastics club and all the way to the mutual aid society [early

forms of mutual health and funeral

insurance]. In colonial times already, especially in harbor cities

such as Philadelphia and New

York, well to-do Germans founded charitable institutions to better assist

newcomers. In the

middle of the nineteenth century, when the first wave of anti-immigrant

Nativism hit, there was a lot of discussion, even among German-Americans themselves,

concerning the positive and negative effects of the innumerable immigrant

organizations that were

operating at full tilt. Were they aiding or hindering integration? A

well-articulated contribution

to the debate was offered in 1857 by Atlantis, the top 1848er

journal:

Singing societies, theater clubs, Free Mason lodges,

political clubs of all parties,

and other organizations are found wherever Germans live, even in the

smaller cities. The

cultivating effects these societies have, however, are  more than dubious

and,

in general, the observation is valid that these clubs degenerate to

the lowest possible levels of taste. They serve no other purpose than

pleasure, by which, however, they hang onto their

membership. Of course, many of these societies, especially

the musical groups, are a means to greater fellowship and they do build

bridges between

Americans and

Germans. The competitive singing festivals held in the East and the

West are welcome opportunities for good fellowship. . . . The first

attempt

at building an organized network of clubs extending all across the

Union was made by the Turner society, which from its earliest

initiatives showed promise for outstanding results in social and

political matters [Anonymous, "Das deutsche Leben in Amerika,"

Atlantis, Jan. 1857].

more than dubious

and,

in general, the observation is valid that these clubs degenerate to

the lowest possible levels of taste. They serve no other purpose than

pleasure, by which, however, they hang onto their

membership. Of course, many of these societies, especially

the musical groups, are a means to greater fellowship and they do build

bridges between

Americans and

Germans. The competitive singing festivals held in the East and the

West are welcome opportunities for good fellowship. . . . The first

attempt

at building an organized network of clubs extending all across the

Union was made by the Turner society, which from its earliest

initiatives showed promise for outstanding results in social and

political matters [Anonymous, "Das deutsche Leben in Amerika,"

Atlantis, Jan. 1857].

The value, especially of the Turner societies, for promoting

interaction between German

immigrants and English-speaking Americans, was articulated in 1886 by the

Chicago-based

socialist journal, Vorbote. The following editorial sharpens the

debate over

the admittance of English-language terminology for gymnastics training at the

Boston Turner society:

English commands, which should be used alongside German

commands only

when necessary, bring American  children onto the gymnastics field. Americans, teachers as

well as

others, can be won over to the cause of German gymnastics only if they

understand fully what's going on. At any rate, the case for our German

culture will be better served if

we attract Americans to our side. On the gymnastics field we can acquaint

them with our German

customs and traditions and, of course, also with our language more

successfully than if we hold them at bay because of our nationalistic

tendency to live in our

own enclaves. If gymnastics is such a good thing, then it is our civic

duty to make it accessible to

Americans as well" [Der Vorbote, July 7, 1886].

children onto the gymnastics field. Americans, teachers as

well as

others, can be won over to the cause of German gymnastics only if they

understand fully what's going on. At any rate, the case for our German

culture will be better served if

we attract Americans to our side. On the gymnastics field we can acquaint

them with our German

customs and traditions and, of course, also with our language more

successfully than if we hold them at bay because of our nationalistic

tendency to live in our

own enclaves. If gymnastics is such a good thing, then it is our civic

duty to make it accessible to

Americans as well" [Der Vorbote, July 7, 1886].

To what extent the Turner societies and other German-American social

clubs actually became

a venue for cultural exchange between Germans, Americans and other

immigrant groups has not

been thoroughly investigated. But if, for example, the history of the

Deutsches Haus-Athenaeum in Indianapolis has any representational value

for Turner clubs

elsewhere, we may hypothesize that a good deal of interaction took place

and continues to do so.

Besides the numerous

clubs

and the mutual

aid societies founded to meet the concrete needs and interests of members

locally, the

German-American National Alliance, a cultural-political umbrella

organization, was founded in Philadelphia in 1900. It got underway at a

time when German immigration

had dropped to a sixty-year low. The task of the Alliance was "to arouse

and promote feelings of

unity within the people of German origin." It was also designed "to spark

the inherent power of

the German-Americans so that they would exert a healthy

influence on, and an energetic defense of, such rightful wishes and

interests as were neither in

opposition to the common good of the country nor averse to the rights and

duties of good citizens

everywhere; to shield German-Americans against nativist attacks;

and to foster good, friendly relations between

America and the Fatherland."

The highest total membership the Alliance ever reported was three million

in 1916. Although

religious organizations tended to stay their distance, the at times

vociferous National Alliance

claimed to act as the "official" lobby of the German-Americans,

however defined. As if reacting on instinct, the Alliance opposed the

very notion of

prohibition as

well as all legislative attempts to enact it into law; it

fought against immigration limits; and it encouraged legislation that

would promote German language instruction in the public schools. At the

same time, the Alliance

encouraged the acquisition of American citizenship and along with that,

at least indirectly, the

learning of English and the study of the Immigration

Commission's citizenship "catechism." Intellectually, however, Alliance

leaders were not up to the challenge

presented by the First World War. On the one hand they propounded

arguments for

neutrality to the Wilson government, and on the other they engaged in

blatant pro-Kaiser

propaganda. Near the end of the war, the Alliance lost even its social

moorings, with the result

that, following Congressional hearings concerning its possible

un-American

activities, it was disbanded by government fiat.

Founded in 1919 as a kind of replacement for the Alliance, the

Steuben Society of America

accepted into its membership only American citizens, used only English as

its official language,

and tried to distance itself from the former national

organization that had fallen into disrepute for its "unpatriotic" stand

on hyphenated Americanism.

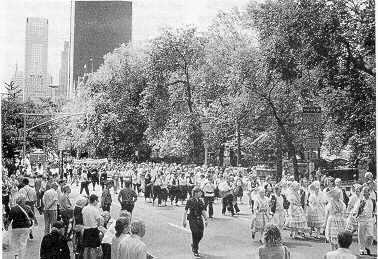

It took until 1958 before the new society initiated its now popular

Steuben Parade in New York

City, an event which since has become a well publicized annual

festivity for German-Americans, including both local dignitaries as well

as visitors from abroad.

The Steuben Society's significance does not lie in the political arena.

Its existence and its activities

make sense rather as a symbolic statement, which

holds true also for the varied small social clubs all across America. In

other

words, many Americans are proud of their German heritage and maintain

memberships in a host

of organizations that range from the traditional "Männerchor,"

"Liederkranz," the "Swabian

Singing Society" and the "Brooklyn Schützen [sharpshooters] Choir"

to the New York Hanseatic Club for businessmen. Made wise through

unpleasant

experiences in the

past, the framers of constitutions and bylaws for these clubs usually

exclude any and all party

politics.

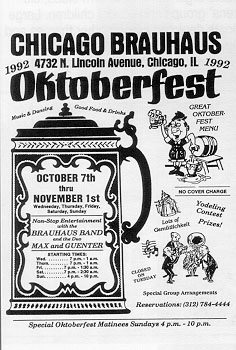

Many of the numerous local German-American clubs and societies, have

long passed their

100th or even 125th anniversaries. But due to the near cessation of

German immigration toward

the end of the 20th century, most German-American organizations have

difficulties recruiting the young for membership. The still growing

interest in "roots," however, has

led to the formation of regional German heritage societies where the

emphasis is less on

"Gemütlichkeit" and more on research and documentation.

Heritage societies take the notion of "German" in its ethno-linguistic or

cultural sense, which then

includes the heritage of all Americans whose roots reach back into the

German-speaking areas of

Europe.

The period for politically significant public displays of Germanness

ended for good with WW I

and the exile of Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918. The celebration of the

Tricentennial of German

Immigration in 1983 gave rebirth to "October 6" as German-American

Day. It has taken its place among non-political festivities celebrated by

ethnic groups across the

United States. With good reason. There remains no trace of the

politically-charged German Day

which was celebrated in many cities from 1883 to 1933. Rivalries

with other immigrant groups and the struggle to win respect from Yankees

have long since passed

into history.

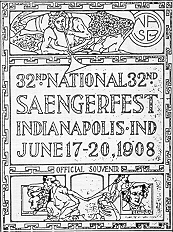

Quite a different mood prevailed in 1849, when the first

Sängerfest competition, held in

Cincinnati, publicly championed the strength and vitality of the Germans,

or even in 1900 in

Brooklyn, when over 6,000 singers from 174 singing societies poured

into the city for a Sängerfest lasting several days. In 1871, on

the occasion of the peace treaty

following the Franco-Prussian War and the founding of the German Empire,

the intentions that lay

behind the four-hour long parade of 100,000 people in Manhattan

were undeniably political. Commanded by Civil War general and

German-American hero,

Franz Sigel, all groups marched proudly: singers, Turners,

Schützenvereine [sharpshooters clubs],

old veteran groups, militia units, secret societies, lodges, brewers

, butchers and other trade union societies, charitable organizations,

reform clubs, citizens' groups

and school children. Large floats depicted among other themes and figures

the "Watch on the

Rhine," Gambrinus (the patron saint of beer),

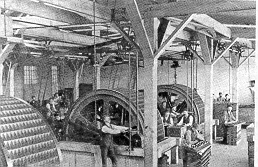

a full-scale brewery, a coal mine, the crown of Charlemagne positioned

across the newly-united

Germany, and a retinue including the Kaiser with his crown prince (and

their escorts).

Festivals and parades that were occasioned by lesser historical

events, but organized by an

ethnic pride that has long since receded, were once perceived -- both

within the group and beyond it

by the general public -- as high points of ethnic array. The

reasons for celebrating were quite varied. There were Schützenfests,

Turnfests, Sängerfests,

Carnival parades, May celebrations, Johannis festivals [St. John the

Baptist Day coincides and is

celebrated with the summer solstice] -- all part of the observance of

annually repeated seasonal festivities. Fests that commemorated great

Germans like Schiller or

Humboldt, as well as the one-event commemorations such as the Peace

Treaty of 1871 or the

Bicentennial (1883) commemorating the first group arrival of German

immigrants in Pennsylvania-all offered an opportunity to promenade the

whole of German ethnic

culture. Contemporaries got the impression of a continuous concatenation

of German

festivities:

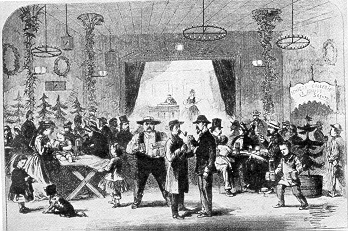

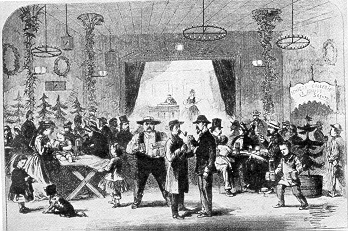

The Germans in New York seem to be the most "advanced"

pleasure-seeking

people on earth. At any rate, they provide more folk festivals in the

course of one year than take

place in all the major cities of Europe in a whole decade. The good folk

s of New York get to enjoy some kind of festival every single day, and

for the most part they all

attend. These festivals last one or several days -- sometimes an entire

week -- and cost a great deal of

time and money. . . . You cannot help but wonder where the

thousands and thousands of working people who attend these festivals get

the time and the money

to pursue so many pleasures [Adolph Wiesner, Geist der

Welt-Literatur,1860. See Conzen, in

Werner Sollors, ed., Invention of Ethnicity (New York, 1989), 24'

ff.].

Many simply indulged in "down-home" nostalgic feelings: "The German

felt

revitalized and stimulated. For a few days he was able to feast on the

most wonderful memories of

bygone happy days . . . and completely abandon himself to the reconciling

magnetism of ennobling song" [Leipziger Illustrirte Zeitung (Aug.

5,1855),152. See Conzen, in

Sollors (1989), 255].

Others saw additional benefits hoped for by the Organizers: "These

festivals afforded

Germans in the company of their fellow countrymen the opportunity to

indulge in the old-time

German style and therein acknowledge that their national traditions and

moral fiber were valid even this far away from their original source." At

the same time, the

festivals afforded "the German element the opportunity to depict itself

to Americans from its most

positive angle; German skills, German strength, German education and

German happy ways ought to enter the open marketplace of American

business and civic

activity, and thereby gradually raise them to a higher level of

dedication" [Meyer's Monats-Hefte, 2 (Dec. 1883), 155. See Conzen,

in Sollors (1989),255]. Likewise, the individual leisure-time behavior

of the German-Americans -- the largest ethnic

group in the

country -- could hardly be kept secret. Sunday afternoons in particular

could turn sour, since any

German's innocent hike, if linked to a visit in a beer garden,

bumped straight into the Puritan Yankee tradition of complete Sunday

rest. In 1851 a German

tourist found his countrymen's behavior somewhat offensive, especially on

Sunday:

Then you have the opportunity to observe the sizable number

of Germans in

the larger cities. You meet crowds of them in the streets and in taverns;

however, most are from

the lower classes, while the upper-crust Germans choose either to stay at

home or to head for their summer retreats out in the country. Working

class and trade union

Americans readily follow the example of the Germans in frequenting

taverns, which greatly

annoys the Puritans and most clergymen throughout America. In some German

taverns in and around New York, the ones that are frequented by trade

union and lower class

workers, you even find Sunday afternoons filled with entertaining music

under the pretext of

being religious in nature. Some tavern keepers at times also try to

offer dancing on Sunday afternoons, but the authorities usually catch up

with them-which results

in a fine for the tavern keeper [A. Kirsten, Skizen aus den

Vereinigten Staaten von Nordamerika,

Leipzig, 1851, 315 ff.].

Attempts by Anglos to regulate the public consumption of alcohol

led to social conflict

again and again. It is a fact that the alcohol question repeatedly

crystallized the ethnic

consciousness of German-Americans. They always interpreted prohibition

attempts on the part of

temperance proponents as an attack on their German sense of freedom and

their traditional way of

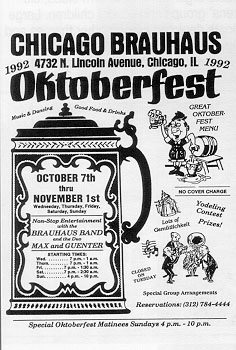

spending leisure time. A Sunday fling to a beer garden in summer and an

evening of gossip in the

local bari -- in Milwaukee in 1860 there was allegedly one bar for every

30 households -- these traditions were defended as being part and parcel

of German culture

and of American civil rights. When limitations were placed on the sale of

liquor across the bar on

Sundays in Chicago in 1889 and when steep license fees won s

upport in local elections, the Germans opened verbal barrages on the

Sabbath idiocy of

snoopy-nosed Yankee priests." The Illinois Staatszeitung [Sept. 9,

1889] mocked them: "Once

that happens, once deadly boredom and pharisaical hypocrisy are trump,

then

Chicago will have become an authentic American city." Nevertheless,

there were at this juncture

more than 1,700 German taverns in Chicago, and in the red-light district

the tavern and the beer

garden were the most likely contact spots.

In all probability, very few of the contentious defenders of

German-American "freedom"

realized just how much or how little tolerance they themselves exhibited

for cultural

diversity -- although they took for granted as their

God-given right that Anglo-Americans and other ethnic

groups would show them tolerance.

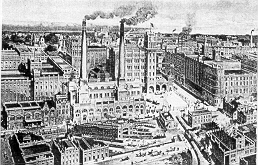

See Theodore Stempfel's 1898

Festschrift, Fifty Years of Unrelenting German Aspirations in

Indianapolis, 1848-1898. Bilingual Edition 1991

(Indianapolis: German-American Center and Indiana German Heritage

Society, 1991),

in particular the speeches on the occasion of the

inauguration of the Deutsches Haus in 1898.

more than dubious

and,

in general, the observation is valid that these clubs degenerate to

the lowest possible levels of taste. They serve no other purpose than

pleasure, by which, however, they hang onto their

membership. Of course, many of these societies, especially

the musical groups, are a means to greater fellowship and they do build

bridges between

Americans and

Germans. The competitive singing festivals held in the East and the

West are welcome opportunities for good fellowship. . . . The first

attempt

at building an organized network of clubs extending all across the

Union was made by the Turner society, which from its earliest

initiatives showed promise for outstanding results in social and

political matters [Anonymous, "Das deutsche Leben in Amerika,"

Atlantis, Jan. 1857].

more than dubious

and,

in general, the observation is valid that these clubs degenerate to

the lowest possible levels of taste. They serve no other purpose than

pleasure, by which, however, they hang onto their

membership. Of course, many of these societies, especially

the musical groups, are a means to greater fellowship and they do build

bridges between

Americans and

Germans. The competitive singing festivals held in the East and the

West are welcome opportunities for good fellowship. . . . The first

attempt

at building an organized network of clubs extending all across the

Union was made by the Turner society, which from its earliest

initiatives showed promise for outstanding results in social and

political matters [Anonymous, "Das deutsche Leben in Amerika,"

Atlantis, Jan. 1857].

children onto the gymnastics field. Americans, teachers as

well as

others, can be won over to the cause of German gymnastics only if they

understand fully what's going on. At any rate, the case for our German

culture will be better served if

we attract Americans to our side. On the gymnastics field we can acquaint

them with our German

customs and traditions and, of course, also with our language more

successfully than if we hold them at bay because of our nationalistic

tendency to live in our

own enclaves. If gymnastics is such a good thing, then it is our civic

duty to make it accessible to

Americans as well" [Der Vorbote, July 7, 1886].

children onto the gymnastics field. Americans, teachers as

well as

others, can be won over to the cause of German gymnastics only if they

understand fully what's going on. At any rate, the case for our German

culture will be better served if

we attract Americans to our side. On the gymnastics field we can acquaint

them with our German

customs and traditions and, of course, also with our language more

successfully than if we hold them at bay because of our nationalistic

tendency to live in our

own enclaves. If gymnastics is such a good thing, then it is our civic

duty to make it accessible to

Americans as well" [Der Vorbote, July 7, 1886].