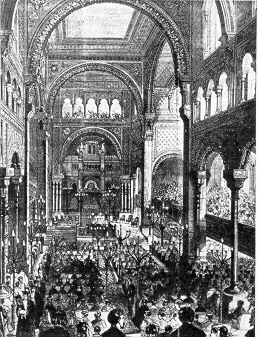

Rough estimates put German immigrants at one-third Catholic and the

other two-thirds

predominantly Lutheran and Reformed. Coparatively small in numbers were German

Methodists,

Baptists, Unitarians, Pietists, Jews and Free Thinkers. For many German

immigrants the parish

church was the center of their social lives.

The prosperity and attractiveness of a community out in the

countryside could be recognized

by its church and school structures. Each was an expression of the

initiative of local immigrants.

In 1869 John

Bauer wrote to his parents in Baden how the residents in his rural

community in Missouri all

contributed to the construction of the school house, for "of course, I

would much rather pay this

sum [$18.25] than live in a neighborhood where the

schools are poor." He went on, "As soon as this is finished, they will

probably build a new church which will naturally cost more than the

schoolhouse. It is not

compulsory, for many rich men don't give a cent for it, although they are

often blessed by

Providence with everything; there are also people here who never go to

church & think more about a nice horse than a fine church. I do not want

to take a back seat here

and if God gives me life and means, I intend to contribute my share. You

don't need to do this in

Germany, but here the government does nothing at all" [Kamphoefner,

News, 167].

Long before public school systems were mandated by state

legislatures, the parish church

was also running a parish school. This holds true especially for the

German-language parish

churches and their private German schools. "The language is the

vessel of faith," is how church leaders explained their approach to parochial

education. They hoped to

ward off any threat to the religion of their children (which they

perceived would originate from

the English-language public schools) by keeping the German

schools under church management. Leaders in the German-speaking Catholic

parishes also built

barricades against what they perceived as a threat of domination by the

Irish-American Catholic

hierarchy. Protestant churches were the primary beneficiaries of

donations from Germany, while the German Catholics in America profited

from the personal

volunteer work of immigrant priests and religious orders. Nuns,

especially Benedictines and

Franciscans, ran their own hospitals, schools and even preparatory

seminaries for the clergy. For example, in Indiana, beginning with the

second half of the

19th century, the sisters of the Catholic teaching orders of St. Francis

and St. Benedict provided

tens of thousands of children with a German Catholic education. Around

the state today, the

sisters still operate numerous schools, although no longer as "German"

institutions.

In colonial times and well into the 19th century, all German-language schools in states such as Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and the Carolinas were operated as parochial schools. Not until 1850 was there any competition from public schools and a new brand of sectarian schools in the densely German settlements of the Midwest and in Texas. Private schools began to be run by Free Thinkers and other non-religious organizations. Because Germans in many towns saw little chance for transmitting either their language or their cultural heritage in the American public schools, they often founded a local German school society that functioned as legal owner of their school.

In some communities, the German schools operated according to new pedagogical principles and had a lasting impact on the American school system. Kindergarten as a pre-school, sports programs at all school levels, music, and manual arts as elements of the regular curriculum were first introduced by so-called radical-democratic German groups, such as the Socialist Turner Societies, an entity known today as the American Turners. In Milwaukee, and later in Indianapolis, this organization had its own Normal College for teachers of physical education. Some well-known schools like the Knapp School in Baltimore and the German-English Academy in Milwaukee existed into the 20th century. Examples of especially progressive schools founded by German immigrant intellectuals were the Rosler von Oels School in New York, the Zion School in Baltimore, the school system founded by Georg von Bunsen in Belleville, Illinois and many manual training high schools which combined academic and vocational education.

Like the Catholic church, the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church was

educationally very active.

It operated a half dozen high schools in a manner similar to a German

gymnasium.

Candidates for

pastoral training who first attended these schools later went on to the

distinguished

German-language Theological Seminary in St. Louis. At the same time, the

Synod maintained two

teacher training colleges to serve its private elementary and high

schools.

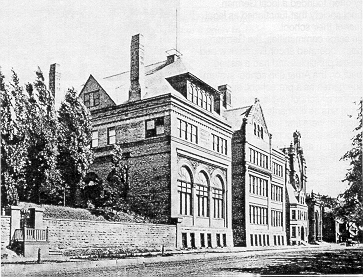

The only secular German-English teacher training institution existed in

Milwaukee from 1878 to 1919. This bilingual institution educated a total

of 335 teachers for instruction in private and public elementary

schools.

Like the Catholic church, the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church was

educationally very active.

It operated a half dozen high schools in a manner similar to a German

gymnasium.

Candidates for

pastoral training who first attended these schools later went on to the

distinguished

German-language Theological Seminary in St. Louis. At the same time, the

Synod maintained two

teacher training colleges to serve its private elementary and high

schools.

The only secular German-English teacher training institution existed in

Milwaukee from 1878 to 1919. This bilingual institution educated a total

of 335 teachers for instruction in private and public elementary

schools.

Particularly in urban settings -- and in spite of efforts to the

contrary -- the forces of integration

would eventually spell the decline of German-language preservation in the

two principal pillars of

language maintenance outside the family: the German church and the German

school. With more and more second and third generation

German-Americans outweighing by far the dwindling replenishment of new

immigrants, the need

and the preference for English became unstoppable. And when, by the late

19th

century, German had become the leading modern foreign language in high

school, many

German-American parents and school boards of non-church-related schools

felt that the expenses

of running

a private school were no longer warranted.

Following the First World War with its massive and

intimidating campaign for Americanization, practically the only

German-language instruction that

continued to exist was in the rural German-language enclaves. On

June 4,1923, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in the case of

Meyer vs. the State of

Nebraska that a knowledge of the German language by  itself

could not be regarded as harmful and

that the right to teach and the right of parents to have

their children taught in a language other than English was within the

liberties guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment [Rippley, 1984, p. 126]. In 1925 the Supreme

Court ruled in the case of

Pierce vs. the Sisters of the Holy Name of Jesus and Mary that children

between

the ages of eight and sixteen

were not bound to attend a public school. But even with such favorable

court decisions, German

schools were on the decline. In 1927 there were still 555 German-American

private schools with

35,000 pupils, but ten years later in 1936 there were only 281

such schools with 17,800 pupils.

itself

could not be regarded as harmful and

that the right to teach and the right of parents to have

their children taught in a language other than English was within the

liberties guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment [Rippley, 1984, p. 126]. In 1925 the Supreme

Court ruled in the case of

Pierce vs. the Sisters of the Holy Name of Jesus and Mary that children

between

the ages of eight and sixteen

were not bound to attend a public school. But even with such favorable

court decisions, German

schools were on the decline. In 1927 there were still 555 German-American

private schools with

35,000 pupils, but ten years later in 1936 there were only 281

such schools with 17,800 pupils.

An unrealized dream of a few German-Americans was to have their own university with German as the language of instruction, which, it was hoped, would have attracted a varied German-language clientele of differing religious and political persuasions. But in spite of German "Kultur" enthusiasm on the part of confessional and non-confessional German-Americans, the sometimes almost militant particularism among the "Krauts" was not conducive to such an enterprise.

Concerning teacher training and other German institutions of higher education in the United States, see LaVern J. Rippley, "The German-American Normal Schools," in Erich A. Albrecht and J. Anthony Burzles eds. German Americana 1976 (Lawrence: Max Kade Document and Research Center, 1977), 63-71.