A nine-lived legend that German almost became the official language of

the United States

persists to this day. Fascinating for Germans, this imagined decision

has been popularized by

German authors of travel literature since the 1840s and propagated by

some American teachers of

German and German teachers of English who are not entirely secure in

their American history. In

reality, this presumed proposition was never brought to the congressional

floor and a vote was

never taken. At the root of the so-called Mühlenberg legend lies

rather a disappointment that

German was not able to hold its ground as a language of daily usage even

in Pennsylvania, except

within small Mennonite, Amish and other sectarian communities. During

both the War of

Independence and the War of 1812, at times when anti-English feelings

were running high,

Americans of German descent comprised less than 9% of the total

population of the United

States. And even in Pennsylvania, where the Germans had settled most

densely, they amounted

to only a third of the entire population. Colonial speakers of English

fought only

for their political independence. They had no stomach for an anti-English

language

and cultural revolution.

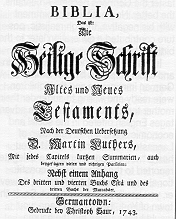

When German-language farmers in Augusta County, Virginia petitioned the U. S. House of Representatives in 1794 for a German translation of the booklet containing the laws and other government regulations -- copies of which had been distributed free in the English language -- officials simply ignored them. Even the bilingual Speaker of the House of Representatives, Frederick Augustus Conrad Mühlenberg, refused to support their modest request. arguing that the faster the Germans became Americans, the better. No doubt, disappointment with his negative, though realistic, posture contributed a generation later to the birth of this legend.

In reality, contemporaries were again

and again surprised by how swiftly

German immigrants and their children

were ready and willing to surrender their

mother tongue for the sake of the advantages English offered in the

social and

economic arena. In the little town of

Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1817 you

heard "nothing but German," a delegate

reported to the Pennsylvania constitutional convention of 1837. "Now,

however, you hardly hear

a word of it. So, in the

town of York, twenty years ago, you

would hear nothing but the bauren

sprache of the country; but now it has all

passed away and you hear nothing but

English spoken. The young Germans

don't wish to continue to speak it." No

wonder that in 1837 there was no majority in favor of alternately hiring

German-speaking and

English-speaking teachers

in the public elementary schools of

Pennsylvania, or for the admission of

German for court proceedings.

Nevertheless the use of Pennsylvania's

German -- better known as Pennsylvania

Dutch -- "reached its climax between

1870 and 1880; it was the everyday language of about 750,000 people, about

600,000 of whom lived in Pennsylvania"

[Jurgen Eichhoff and Marion Lois

Huffines, in Trommler (1985), 224ff.,

241ff.].

The following example of linguistic

assimilation mirrors the experience of

millions of German-Americans. A successful farmer and former carpenter

emigrated from a Mosel

Valley village to his

relatives near Detroit in 1857, and in

1888 wrote back to his relatives in

Germany: "Our eldest son Peter is now

19 years old and a first-class worker. He

can do all the carpentry work according

to plans. . . . What I learned in Germany

with hard work and much effort he can

learn here almost at a glance. Although

our children all speak German and learn

to read and write German at school, they

are more familiar with English since it is,

after all, the language of the country"

[Kamphoefner, News, 200]. This perfectly

natural assimilation process, accepted by

the majority of German immigrants. who

were seeking economic prosperity, was

the primary cause for the disappearance

of German as a viable vehicle of daily

communication in North America. World

War I, with its acute phase of cultural

suppression, simply accelerated this

inexorable process.

During the century preceding the First World War, a pluralistic German-language culture existed in America; as late as 1910 an estimated nine million people in the United States still spoke German as their mother tongue. They formed the broad basis for readership of a large variety of German-language newspapers and publications, supplied membership for German-language clubs and parishes, and were the force behind assorted attempts at offering German as a language of instruction, or at least as a foreign language elective, in the public schools.

Some states mandated English as the exclusive language of instruction in the public schools, while Pennsylvania and Ohio in 1839 were first in allowing German as an official alternative, even requiring it on parental demand. Some public and many private parochial schools taught exclusively in German throughout many decades, mostly in rural areas. But only in a few large cities, such as Baltimore, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, was it ever feasible to operate bilingual public schools, while German-Americans in Buffalo fought for it in vain in the 1860s . In St. Louis the bilingual public schools in the long run achieved the opposite of what the culturally-conscious German-Americans had expected. While four out of five children of German-American families were enrolled in a private (meaning German-language) school in 1860, in 1880 four out of five such children were enrolled in a public bilingual school. Rather than enabling those children to retain their German, the bilingual schools apparently did more to accelerate the acquisition of English.

Typically, by about 1900, German was no

longer used as a primary or co-equal language of instruction in the

larger cities,

although it was very popular as a foreign

language elective, even for children who

were not of German ancestry. In Chicago,

for instance, only 15,000 of the 40,000

taking German in 1900 were of German

background.

Elementary school German-language enrollments reached their peak between 1880 and 1910. Around 1881, more than 160,000 pupils were attending German Catholic schools; in the same year 50,000 attended Missouri Synod Lutheran schools, which 20 years later tallied around 100,000. In Evangelical and Reformed schools there were about 20,000 children. And yet, only one-third to one-half of all baptized German Catholic or Lutheran children attended any parochial school. Of about a half million pupils counted by the German- American Teachers Association around the turn of the century, 42 percent were attending public schools, more than a third of them Catholic, 16 percent Lutheran, and the remaining seven percent Evangelical or other private schools. Hidden in these overall impressive statistics are, of course, wide-ranging variations, depending on which specific local area is being assessed.

Since the 1880s, resistance to German as a principal or co-equal language of instruction increased markedly. Illinois and Wisconsin tried in 1889-90 to limit its use, even in the private schools, although without much practical success. According to the new Bennett Law in Wisconsin, a minimum of 16 weeks in the school year was now to be dedicated to English-language instruction, and subjects like reading, writing, arithmetic and American history were to be taught wholly in English. In a quick and passionate reaction to this legislation, the Lutherans and Catholics formed an alliance to fight this perceived attack on their parochial schools. In the very next election, the Lutheran-Catholic coalition effected a quick repeal of these state laws, albeit temporary.

In their endless debates concerning the language question, German- Americans repeatedly bemoaned the lack of parental commitment for German-language retention by their children. The Social Democratic-oriented Deutsch-Amerikanische Buchdrucker-Zeitung (Oct. 16, 1902), under a headline "Deutsch in Amerika" [German in America], had this to say:

"Honor the German language! For the spirit of your forefathers is preserved in its words!" This saying has been enshrined in glass encasements or in picture frames in many a Singer or Turner hall. At many German festivals it is recited proudly with heavy emphasis on the spirit of our forebears. But in everyday life the hallowed words of the poet have had little effect. Parents sometimes grumble about the neglect German-language instruction suffers in the public schools. Some are provoked by the fact that their children who take German are sometimes deliberately denied promotion to the next grade, and they rationalize that the entire American school system is infested with Nativism. Their anger is justified! Only they forget that they themselves are primarily to blame if their children make only minimal progress in the mother tongue. German parents in America should teach their children to learn and to love the German language. They should tell them about the great deeds which the German spirit has wrought. As long as they fail to do just that, as long as they look on indifferently while their children at home speak and read almost exclusively in English, they should not be surprised if their children, even those to whom the opportunity is offered to have German-language instruction in the public schools, have very little excitement for it."

In every immigrant generation, complaints surfaced about a loss of the German language, but never as often as around 1900. When addressing the German School Society of Cleveland at its annual meeting in 1910, Pastor Karl Weiss avowed that three institutions -- the school, the family, and the Verein [club] -- were the great nurseries for the German language in his adoptive Fatherland:

We demand for the children in our schools a brand of German language instruction that is sufficient both qualitatively and quantitatively; not that we want German placed above English -- this would be foolish and unreasonable -- for we realize that English is the language of our country and that a thorough knowledge of English is absolutely necessary for our children. No, we do not decry the language of the American, nor of anybody else; and in this respect we are again loyally dedicated to our new homeland, our American adoptive fatherland, and we know our duties as patriotic citizens.

But we do want our children and their children in their new homeland to get to know the wealth and value of the German spirit and of German culture, and we would like them to preserve it as much as possible. Our children should get to know what they owe to their German origins. They should internalize it so that they may look back with pride on the country of their forefathers, to a country and a civilization that has distinguished itself among all peoples on earth in science, art and literature, in commerce and industry as well as in all other spheres of life, and a culture that for centuries has had a most beneficial influence on this new continent. . . .

The German mother tongue is the only means by which our children can gain a correct and true understanding for the significance of this great people from whom they or their parents descended; and therefore we want this language preserved for them; therefore we advocate German-language instruction in the schools to which we are sending our children. With and through the language, they should acquire the good, the true and the beautiful of the German way of life, of the German spirit, of the German character, of German traditions and of the German philosophy of life, by which they will become ever better Americans, by which they will become ever more valuable citizens of this great republic. . . .

German at home! That should be the highest avocation and the greatest pride of all German fathers and mothers. No matter how thorough and effective German-language instruction in the school may be, the soul, the intimacy and the depth of our mother tongue reaches its most tender expressiveness above all at home in the bosom of the family. Let the English language serve us in public life, in daily business dealings -- but at home, in the beloved home, in the sacred family circle, there let the sweet sounds of our cherished mother tongue echo forth always; for wherever this blessed medium disappears from the home, there the German character will also vanish [Karl Weiss, in Der Freidenker, May 15, 1910].

The First World War drew a sharp cutoff line for German-language

instruction in the entire country, and the total ban of German hit some

groups particularly hard. For the Missouri Synod Lutherans, the war and

postwar hysteria in some states interdicted

even the teaching of Lutheran Bible exegesis in German. In the words of

the state legislature of Nebraska in April 1919: "No person, individually

or as a teacher, shall, in any private, denominational, parochial or

public school teach any subject to any

person in any language other than the English language." One state

representative typified the majority opinion when he said: "If these

people are Americans, let them speak our language. If they don't know it,

let them learn it. If they don't like it, let

them move. . . ." It was this law the U. S. Supreme Court declared

unconstitutional -- but not until 1923 -- thereby restoring the right of

Americans to learn and be instructed in a foreign language (Nebraska vs.

Meyer) [Rippley, 1984, 125].

In 1970 more than six million Americans reported that they had learned German as their first language. However, this statistic gives no clue as to their current ability to speak, read, or write in German. But a good indicator is the 1980 total of subscriptions to German-language newspapers and magazines: 300,000. These break down into two daily papers, 23 weeklies, 15 monthlies and 12 other periodicals [Fishman in Trommler (1985), 256; 258]. Often extenuating circumstances cloud the picture. Estimates put today's number of actual speakers of German in Texas at 70,000. Dialect variations of German are still spoken by some 120,00 Mennonite and Amish groups concentrated especially in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Indiana. Hutterites living in 229 Bruderhof colonies -- New York, South Dakota, Montana and in the Canadian prairie provinces -- add another 22,000. In Wisconsin, where over 50 percent claim German heritage, there is reportedly "not a single area where German is heard as the everyday language in the public domain. To be sure, many older persons in areas heavily settled by Germans are still able to speak the language. But they rarely do. Many of those born before about 1920 report that they were unable to speak a sentence of English until they learned it in school" [Jürgen Eichhoff, in Trommler (1985), Vol. l, 233].

The World War I-effect on the use of German at home and on the German heritage in general is perhaps best expressed by author Kurt Vonnegut in his autobiographical Palm Sunday:

. . .the anti-Germanism in this country during the First World War so shamed and dismayed my parents that they resolved to raise me without acquainting me with the language or the literature or the music or the oral family histories which my ancestors had loved. They volunteered to make me ignorant and rootless as proof of their patriotism [New York: Delacorte Press, 1981, 21].

In 1981 when a representative of the German Embassy brought greetings to a festival gathering of the German clubs of Baltimore, he did the right thing by speaking in English, as did the master of ceremonies. And the current status of the German language in American universities was realistically assessed when the organizers of the academic conference dealing with "300 Years of German Immigration," held in 1983 at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, determined that English would be the working language. It was in English, too, that President Carstens of the Federal Republic of Germany delivered his words of greeting.