The American founding fathers wanted to establish a national state

which, like Great Britain, would be held together by a national language

and characterized by a national culture. Of course, they kept the country

open to immigrants, but they did not

view ethnic pluralism as a goal worthy of support. Open borders for them

was not analogous to splintering the population into a mosaic of ethnic

groups.

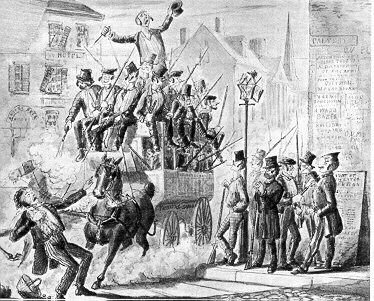

Mass immigration from Ireland and the German-speaking countries,

beginning in the 1840s and continuing in the following decades, unleashed

a fear that the traditional character of the Euro-American society, its

Anglo-conformity and its Protestantism would

be endangered by the uncontrolled mass influx of poor, uneducated, and

for the most part Catholic immigrants who were presumed to be incapable

of democratic principles. Of the 23 million U. S. population in 1850,

almost 10% had been born abroad. This

low average figure, however, in no way expresses the threat perceived

from the dense centers of foreigners in the immigrant districts of some

large cities.

Mass immigration from Ireland and the German-speaking countries,

beginning in the 1840s and continuing in the following decades, unleashed

a fear that the traditional character of the Euro-American society, its

Anglo-conformity and its Protestantism would

be endangered by the uncontrolled mass influx of poor, uneducated, and

for the most part Catholic immigrants who were presumed to be incapable

of democratic principles. Of the 23 million U. S. population in 1850,

almost 10% had been born abroad. This

low average figure, however, in no way expresses the threat perceived

from the dense centers of foreigners in the immigrant districts of some

large cities.

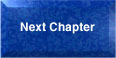

The 4.9 million immigrants who arrived from Europe between 1830 and 1860,

among them 1.36 million German-speakers, met head-on with a well-defined

"Americanism." The conflict was accentuated when several Midwest states

started to grant voting

privileges well before the five year waiting period for citizenship had

transpired. In Minnesota, a male adult got the right to vote practically

upon arrival.

Only four months had to elapse after he declared his intention to become

an American citizen. Using all available xenophobic

arguments, the immigrant-bashing nativist American Party, popularly

called the Know-Nothings, tried to extend the waiting period for

naturalization and for voting to 21 years instead of the five required by

law. In addition, immigrants were

to be permanently excluded from holding

public office; and the poor, those with criminal records, and the loyal

subjects of a "foreign power" -- above all members of the Roman Catholic

Church -- were not to be admitted into the country at all.

The 4.9 million immigrants who arrived from Europe between 1830 and 1860,

among them 1.36 million German-speakers, met head-on with a well-defined

"Americanism." The conflict was accentuated when several Midwest states

started to grant voting

privileges well before the five year waiting period for citizenship had

transpired. In Minnesota, a male adult got the right to vote practically

upon arrival.

Only four months had to elapse after he declared his intention to become

an American citizen. Using all available xenophobic

arguments, the immigrant-bashing nativist American Party, popularly

called the Know-Nothings, tried to extend the waiting period for

naturalization and for voting to 21 years instead of the five required by

law. In addition, immigrants were

to be permanently excluded from holding

public office; and the poor, those with criminal records, and the loyal

subjects of a "foreign power" -- above all members of the Roman Catholic

Church -- were not to be admitted into the country at all.

The unsettling result of nativism in Massachusetts -- nativists were

often also pro-temperance and pro-slavery -- motivated Carl Schurz in

1859 to deliver his oft-quoted patriotic sermon on "True Americanism." At

the time, the Massachusetts legislature

was proposing an amendment that would have barred immigrants from voting

for two years after naturalization. Schurz attacked this distrust as

irreconcilable with basic American

values: "True Americanism, tolerance and equal rights will peacefully

overcome all that is not reconcilable with the irresistible strength of

our institutions." Like dozens of German-American publicists of his

generation and his political persuasion, Schurz tried to couple a

realistic recognition of the forces of assimilation, especially the

Anglo-American political culture, with a defense of the intrinsic values

of his own ethnic group. Reacting to the nativists,

the Forty-eighters made a substantial contribution to the "invention" of

a pluralistic model for a more gentle integration of the immigrants.

values: "True Americanism, tolerance and equal rights will peacefully

overcome all that is not reconcilable with the irresistible strength of

our institutions." Like dozens of German-American publicists of his

generation and his political persuasion, Schurz tried to couple a

realistic recognition of the forces of assimilation, especially the

Anglo-American political culture, with a defense of the intrinsic values

of his own ethnic group. Reacting to the nativists,

the Forty-eighters made a substantial contribution to the "invention" of

a pluralistic model for a more gentle integration of the immigrants.

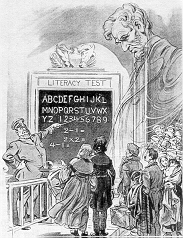

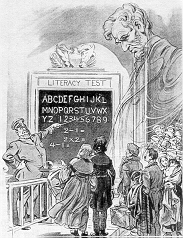

Only in the face of the nation's divisive North-South conflict over

the expansion of slavery west of the Mississippi after 1856, did the

nativist American Party lose political influence without having achieved

its objective. However, if

anti-immigration agitation at this time had

not been overshadowed by the growing North-South controversy, then the

first federal laws curtailing immigration from Europe would probably have

been promulgated long before the literacy tests of 1917 acted as a retardant.

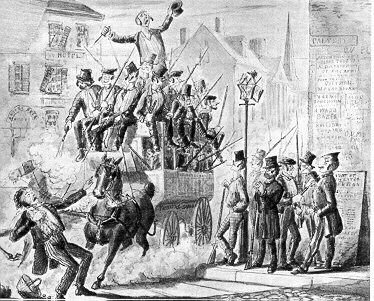

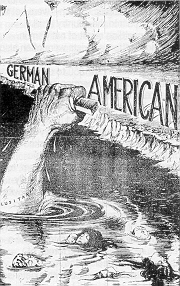

Following

the War of Secession, and especially after the 1877 reintegration of the

South, American nationalism grew stronger than

ever before. In the following decades the United States identified with

Anglo-Saxon racist and superiority attitudes, with a strategy of naval

supremacy in the Pacific, and with Protestant missionary zeal in order to

justify its participation in the great

power rivalry for colonial possessions. Before America's entry into the

First World War, therefore, the public activities of pro-Kaiser

German-Americans and of other large polyglot immigrant groups in many big

cities reminded President Wilson,

Theodore Roosevelt and other vocal American "preparedness" supporters of

certain signs of malfunction in the "melting pot." Meanwhile, the orgies

of European nationalism also aroused America's nationalism with the

result that in 1916 a massive Anglo-Americanization

campaign was launched. The resulting "loyalty" hysteria that accompanied

the United States entry into the War led to an accelerated end of

organized German-American culture.

Following

the War of Secession, and especially after the 1877 reintegration of the

South, American nationalism grew stronger than

ever before. In the following decades the United States identified with

Anglo-Saxon racist and superiority attitudes, with a strategy of naval

supremacy in the Pacific, and with Protestant missionary zeal in order to

justify its participation in the great

power rivalry for colonial possessions. Before America's entry into the

First World War, therefore, the public activities of pro-Kaiser

German-Americans and of other large polyglot immigrant groups in many big

cities reminded President Wilson,

Theodore Roosevelt and other vocal American "preparedness" supporters of

certain signs of malfunction in the "melting pot." Meanwhile, the orgies

of European nationalism also aroused America's nationalism with the

result that in 1916 a massive Anglo-Americanization

campaign was launched. The resulting "loyalty" hysteria that accompanied

the United States entry into the War led to an accelerated end of

organized German-American culture.

Mass immigration from Ireland and the German-speaking countries,

beginning in the 1840s and continuing in the following decades, unleashed

a fear that the traditional character of the Euro-American society, its

Anglo-conformity and its Protestantism would

be endangered by the uncontrolled mass influx of poor, uneducated, and

for the most part Catholic immigrants who were presumed to be incapable

of democratic principles. Of the 23 million U. S. population in 1850,

almost 10% had been born abroad. This

low average figure, however, in no way expresses the threat perceived

from the dense centers of foreigners in the immigrant districts of some

large cities.

Mass immigration from Ireland and the German-speaking countries,

beginning in the 1840s and continuing in the following decades, unleashed

a fear that the traditional character of the Euro-American society, its

Anglo-conformity and its Protestantism would

be endangered by the uncontrolled mass influx of poor, uneducated, and

for the most part Catholic immigrants who were presumed to be incapable

of democratic principles. Of the 23 million U. S. population in 1850,

almost 10% had been born abroad. This

low average figure, however, in no way expresses the threat perceived

from the dense centers of foreigners in the immigrant districts of some

large cities.

values: "True Americanism, tolerance and equal rights will peacefully

overcome all that is not reconcilable with the irresistible strength of

our institutions." Like dozens of German-American publicists of his

generation and his political persuasion, Schurz tried to couple a

realistic recognition of the forces of assimilation, especially the

Anglo-American political culture, with a defense of the intrinsic values

of his own ethnic group. Reacting to the nativists,

the Forty-eighters made a substantial contribution to the "invention" of

a pluralistic model for a more gentle integration of the immigrants.

values: "True Americanism, tolerance and equal rights will peacefully

overcome all that is not reconcilable with the irresistible strength of

our institutions." Like dozens of German-American publicists of his

generation and his political persuasion, Schurz tried to couple a

realistic recognition of the forces of assimilation, especially the

Anglo-American political culture, with a defense of the intrinsic values

of his own ethnic group. Reacting to the nativists,

the Forty-eighters made a substantial contribution to the "invention" of

a pluralistic model for a more gentle integration of the immigrants.