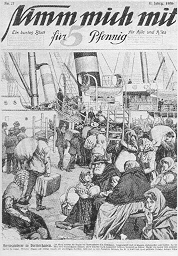

The fate of immigrants, refugees, and migrant workers was experienced

by the more than seven million Germans who emigrated to America over a

period of three centuries.

Their experiences ought not be forgotten. For these lessons from America

can be learned and adapted by nations faced with large-scale immigration

today.

These include Germany, where the flood of non-German-speaking

immigrants -- with their clubs, houses of worship, schools and newspapers

in inner city neighborhoods -- is widely and at times harshly criticized

as a

misdirected development.

In reality, however,

these practices of present-day immigrants resemble age-old approaches

that German immigrants to America implemented successfully in the decades

before they or their children and grandchildren became fully Americanized.

misdirected development.

In reality, however,

these practices of present-day immigrants resemble age-old approaches

that German immigrants to America implemented successfully in the decades

before they or their children and grandchildren became fully Americanized.

As the following depiction of the American experience will show, one

key element for the success of the American policy of integration -- at

least with regard to most European immigrants

-- rested on the political

belief that every male adult in good standing and after only five years

of residence was to be entitled to full citizenship, even with the

handicap of little knowledge of English and just a smattering of American

civics. Once a citizen, the lowly alien found himself transformed in a

sought-after voter. Of course, undergirding American policy on

immigration and assimilation was the unbounded faith in the ideal of a

"country for the oppressed," or as formulated with great exuberance by

the idealistic revolutionary Thomas Paine in the nation's

birth year of 1776, "asylum for mankind."

No one knows the number of German-Americans today. For no one can

determine whether somebody with a German grandmother and a grandfather

from Luxembourg on his mother's side, with an Irish grandmother and an

Italian grandfather on his father's side, and with parents who simply

consider themselves "American" (especially if they speak only English) is

German, Irish, Italian, or what?

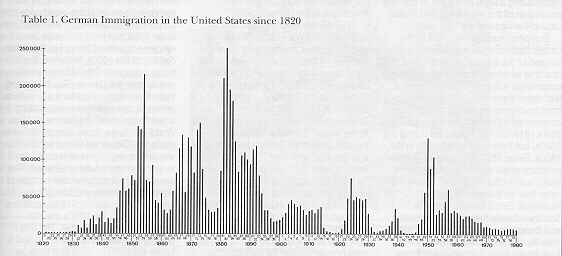

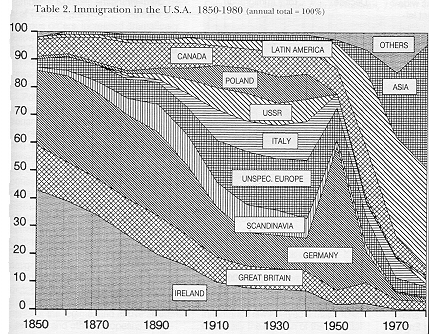

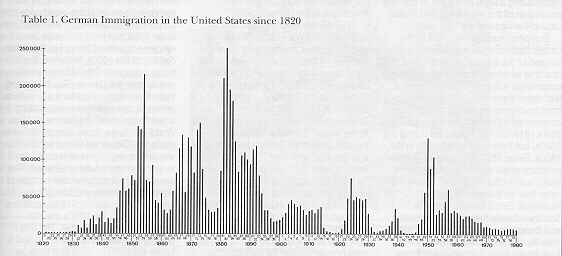

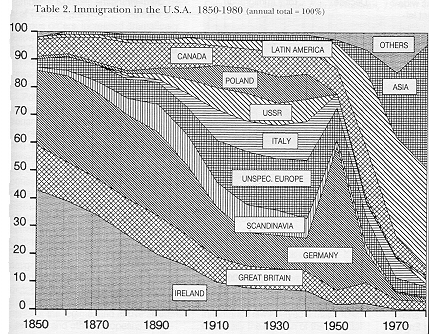

[Source: Based on the U.S. Census Bureau's Historical

Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Series C89-199,

and the annual Statistical Abstract of the United States since

1971. Designed by H.-J. Kaemmer.]

The figures of 50 or 60 million German-Americans reported in the

press after the 1980 census is based on a statistical game that is at

best questionable. In that year the census asked about the country

[countries] of origin of each individual, or his

or her ancestors. Of the 226 million Americans, 17.9 million responded

with "Germany." Additionally, 31.2 million reported that there were also

Germans among their ancestors.

Altogether, a total of 49.2 million

Americans, or 21.7% of the total population, claimed to have had Germans

among their forefathers. It would, of course, make no mathematical sense

to try to compare this figure with those of other nationalities because

someone who reported "German-Irish," for instance, would be enumerated

twice. However, if we play the statistical game of nationalities a bit

anyway --

just to get some graphic sense of the "German element" -- then we

must use this questionable figure of nearly 50 million Germans as a

comparison to the likewise debatable statistic of 101.4 million people

who reported England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland as their ancestral

homes.

The fact remains that no one knows just how many "German" Americans there

are today. What the melting pot has put together, statisticians can no

longer untangle.

With a degree of certitude, however, we can say that the Germans who

were among the immigrants to the United States between 1820 and 1970

amounted to about 15% of the total, and that, since the 17th century,

about seven million people born in the former states of Germany settled

in what is now the territory of the United States. We know too that the

percentage of German-speakers was never large enough that German might

have become the official or second language of any state in the Union.

Nevertheless, the stubborn legend that on one occasion just a single vote

caused German to lose the battle in becoming the official language of the

United States simply will not fade. More about this

in the section on the language question.

The year 1683 is rightfully celebrated as the beginning of group

immigration from the German states. On October 6, 1683, thirteen Quaker

families from Krefeld arrived in Philadelphia. From the outset, their

settlement on the northern outskirts of Philadelphia was called

Germantown.

From then on, the tolerant Quaker colony of Pennsylvania

served as a beachhead for the immigration of pietistic and other

Protestant minorities, notably dissidents of the Reformed and Lutheran

persuasion.

When the first American census was taken in 1790,

Pennsylvania's German population was put at 225,000 which amounts to a

third of the state's entire population.

If we further count those Germans

who in the course of the 18th century settled in the English colonies of

New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia and South Carolina, especially

those from the Palatinate, Baden and Wurttemberg, and include their

children,

then Americans of German origin were about 9% of the total

population of the youthful United States around the close of the 18th

century.

European mass immigration to the United States began in earnest only

after the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815, at a time when unimpeded

transatlantic commercial shipping resumed.

Soon a first major wave of

20,000 emigrants from southwestern Germany took place, occasioned by

major crop failures in the years 1816-17. The figures fell during the

1820s, but increased significantly in the 1830s.

Since 1832, the areas of

German emigrant origin shifted gradually to the West, later to the

Northwest, and

in the latter third of the century to the Northeast. Small farmers from

the Southwest were followed by craftsmen and those engaged in the cottage

industries, by day laborers and eventually by farm hands from Germany's

Northeast.

As time went by, immigrants from all regions of the German

Empire arrived in the United States where, allegedly, German dialect

barriers between Bavarians and East Prussians were occasionally overcome

with the help of English.

The first peak of German immigration to North America came in the

year 1854, when more than 220,000 arriving Germans were registered in

American ports. Decisive factors that unleashed this wave of emigration

were the repeated crop failures that began

in 1846 in southwestern Germany, especially potato rot. In the wake of

the failed Revolution of 1848, according to rough estimates, some 6,000

political refugees made the transatlantic trek, the majority of whom had

first sought interim sanctuary in Switzerland, France or England. To be

sure, these "Forty-eighters" amounted to only a fraction of the total

immigration during this decade. But taken together with the political

refugees of the post-Napoleonic restoration period during the "Thirties,"

these expatriates in the years that followed 1848 represented the

prototypes of the well-educated, liberal -- if not radical-democratic --

German-Americans in the United States.

With the recession of 1857 and the American Civil War (1861 -1865),

immigration declined substantially. After the Recovery following the war,

immigration again dipped as a result of the economic downturn of 1873.

But in spite of the founding of the "Second German Empire" in 1871,

following the Franco- Prussian War, and the boom this created in the

unified Germany, 1882 saw the highest number of German immigrants in a

single year, with over 250,000 registered arrivals. A million and a half

departed from the Empire during the 1880s -- more than in any other

decade before or

after. Around 1900, however, the figures dropped to the level of the

1830s. A booming Imperial German industry was now able to provide jobs

for the surplus rural population and for

the craftsmen whose line of work

had been taken over by machines. In fact, more people came to Germany

during this period than left it; particularly Polish emigrants found work

in the coal region of the Ruhr Valley.

After World War I, the age of unlimited European immigration to the

United States came to an end. Newly-enacted immigration quota laws for

the years 1924 and 1929 limited immigrants from the "Weimar Republic" to

only 25,957 per year.

Because of the world-wide economic crisis of the

1930s, this quota was never lifted, not even to rescue Jewish refugees

from Nazi terror. For the entire decade of the 1930s, therefore, the

statistics show only 119,107 legal immigrants from the German Reich --

among them thousands of intellectuals, writers, artists, actors and

musicians,

making this a real "brain drain" for Germany. After World War II,

generous exceptions were made for "Displaced Persons," German war brides

and others who could no longer envision a future

in Europe. This amounted to a considerable number of postwar emigrants

and brought about another "brain drain" of highly qualified persons

during the 1950s and 60s.

During these two decades, 786,000 Germans

crossed the Atlantic to find a better standard of living and to

experience the professional advancement they could not achieve in the

hidebound structure of West German science and industry,

prior to the sweeping cultural liberalization of the late 1960s.

[The twelve layers illustrate the composition of the annual

immigration waves, not the actual numbers of immigrants. Clearly showing

is the decline of the German share beginning in the 1950s, the first

decade of West Germany's "economic miracle" of

recovery after World War II.]

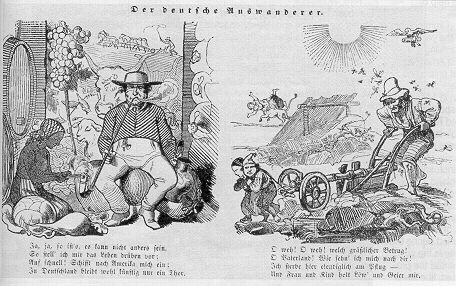

Concerning the number of return migrants -- those who abandoned America

in disappointment -- there has been a great deal of speculation. But

statistical evidence is unavailable, with the exception of a few regional

and short-term investigations.

According to rough estimates based on

Hamburg ship rosters, the figures hover around 4.7% for return migrants

in 1859 and up to nearly 50% for the recession year of 1875.

The statistics are not reliable because the passenger lists do not

distinguish between those who were traveling back and forth, such as

businessmen, seasonal workers, traveling journeymen, short-term visitors,

widows who were taking their fortunes to live out their days back in

Germany, and the truly disappointed who were genuine return migrants.

What is certain is that during periods of weakness in the American

economy, many of the disillusioned returned to Germany.

misdirected development.

In reality, however,

these practices of present-day immigrants resemble age-old approaches

that German immigrants to America implemented successfully in the decades

before they or their children and grandchildren became fully Americanized.

misdirected development.

In reality, however,

these practices of present-day immigrants resemble age-old approaches

that German immigrants to America implemented successfully in the decades

before they or their children and grandchildren became fully Americanized.