Gerry Adams Press Conference1

Fall Road, Belfast

(July 25, 1995)

It appeared that the "Irish Troubles" were intractable. And yet, on August 31, 1994, the "Provisional" Irish Republican Army suddenly went on a unilateral ceasefire and opened the door to a negotiated settlement of the "Irish Troubles." The promise of a quick resolution of the conflict faded, however.

In March of 1995, the British formally put forward the demand that the Provisional IRA decommission weapons before Sinn Féin, the Provisional IRA's political wing, would be allowed to participate in peace talks. The Provisional IRA responded that "pre-conditions" had not been raised prior to the ceasefire and Sinn Féin demanded inclusion in a peace process. Almost a year into the ceasefire (late July 1995), Sir Patrick Mayhew, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, raised the possibility of an international commission that would oversee decommissioning. In a press conference outside of Sinn Féin offices on the Falls Road, Gerry Adams, President of Sinn Féin, stated that if the commission was a way to fulfill the pre-condition, then "it's patently a non-starter." The full press conference, during which Adams responds to questions from journalists, is available here: https://iu.mediaspace.kaltura.com/media/t/1_x7uysu7v

The press conference is followed by approximately two and half minutes of video of scenes in Belfast City Centre and West Belfast on June 25, 1997.

Carrickmore, County Tyrone2

Navan, County Meatch, July 1995 (Screenshot)

Background

Beginning with community violence in August 1969, the "Irish Troubles" claimed more than 3,500 lives. The violence was complex and involved Irish Republican paramilitaries, who sought to unite Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland and create a democratic, socialist republic; Loyalist paramilitaries, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom; and the security forces, including the British Army and the Northern Ireland police. The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) was the largest republican paramilitary organization and was responsible almost 1,800 of the fatalities. It was a major political event when they announced that "as of midnight, August 31, there will be a complete cessation of military operations."3

The announcement, which was a surprise to many observers, flowed from a series of events that began in 1989 when Sir Peter Brooke, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, stated in a press conference that "it is difficult to envision a military defeat" of the Provisional IRA.4

Brooke followed up with a speech in January 1990 in which he called for inter-party talks among the "constitutional" political parties in Northern Ireland, which excluded Sinn Féin because of its close association with the Provisional IRA. In the fall of 1990, Martin McGuinness, a prominent Sinn Féiner and former Provisional IRA Chief of Staff, met secretly with Michael Oatley, an agent of British intelligence with substantial experience in Northern Ireland. Additional IRA-British meetings occurred in the background while constitutional politicians in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and Great Britain discussed the future of Ireland. In December 1993, in an attempt to "foster agreement and reconciliation," Taoiseach Albert Reynolds and Prime Minister John Major issued a "Joint Declaration for Peace" (the Downing Street Declaration) that offered a series of principles that might provide a foundation for a negotiated settlement.5 Six weeks after the Provisional IRA's unilateral ceasefire, the Combined Loyalist Military Command announced that Loyalist paramilitaries would go on ceasefire. It appeared that a lasting peace was at hand.6

All-party negotiations were not forthcoming, however. In March 1995, Sir Patrick Mayhew, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, laid out three pre-conditions for the IRA before Sinn Féin would be invited to peace talks:

- A willingness to disarm progressively;

- A common understanding of what decommissioning would actually entail; and,

- As a sign of good faith and demonstration of the practical arrangements, the actual decommissioning of some weapons.7

In response, the Provisional IRA complained that the British had not mentioned pre-conditions in the discussions that preceded its ceasefire and Sinn Féin began organizing non-violent protests demanding that they be included in all-party talks.8

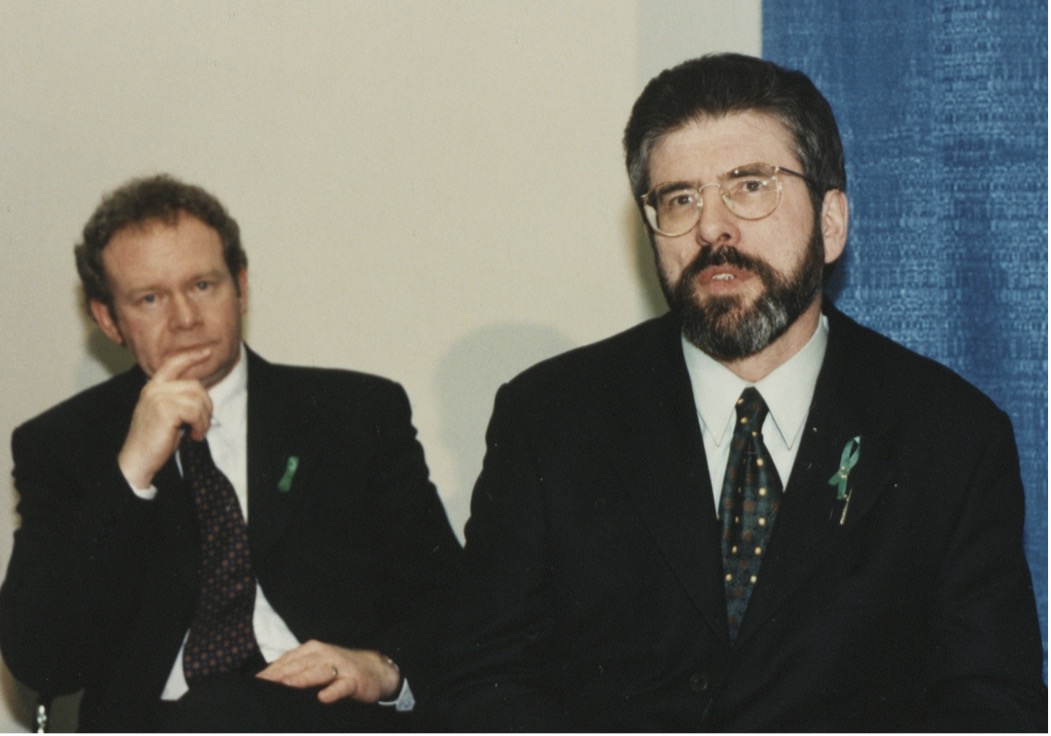

In May 1995, Patrick Mayhew met briefly with Gerry Adams in Washington, D.C., and Martin McGuinness led a Sinn Féin delegation that met with Michael Ancram, the Political Development Minister at the Northern Ireland Office. It was the first official meeting between Sinn Féin and British representatives in decades. Unfortunately, the impasse persisted: the British demanded IRA decommissioning and the reply, in the words of Martin McGuinness, was "there's not a snowball's chance in hell of any weapons being decommissioned this side of a negotiated settlement."9

In July, successive events further undermined the prospects for peace. Early in the month, and in contrast to the treatment of long-term IRA prisoners, Lee Clegg (a British soldier sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Thomas Reilly in Belfast), was released and allowed to return to the British army after only four years in custody. Clegg's release sparked riots in Nationalist areas of Northern Ireland. Then, in the run-up to the annual July 12 celebrations, there were major Nationalist–Unionist confrontations at Drumcree Church outside of Portadown and along the Ormeau Road flashpoint in Belfast. On July 18, 1995, Sir Patrick Mayhew and Michael Ancram met secretly for two hours with Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, but there was no progress.10 After the meeting became public, Adams stated that there was "no real possibility" of IRA decommissioning and added that Sinn Féin would continue to organize protests demanding inclusion in negotiations.11

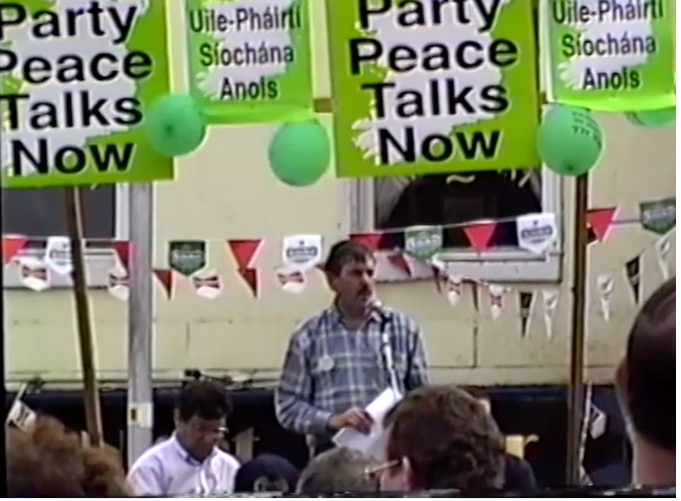

On Friday, July 21, the RUC used batons against a Sinn Féin demonstration in the Belfast City Centre and arrested eight people.12 The next day, Sinn Féin held an "All-Party Peace Talks Now" rally in Navan, County Meath that was addressed by Mick Reilly, a former political prisoner and member of the Navan Urban District Council, and Mitchel McLaughlin, National Chairperson of Sinn Féin (video of the rally is available here: https://iu.mediaspace.kaltura.com/media/t/1_tv0fj90d).13

With tension mounting, Sir Patrick Mayhew broached (first with Dick Spring, the Irish foreign minister) the possibility of creating an international commission that would supervise the decommissioning of Provisional IRA and Loyalist paramilitary weapons.14 In an article published in An Phoblacht/Republican News and The Irish People (based in New York), Gerry Adams framed the development with, "Now, as we approach a crisis, created by a British demand, London, while retaining this absolutist position, is suggesting off the record that the idea of a commission may solve this problem."15 This was the context when, on Tuesday, July 25, Gerry Adams held a press conference outside of Sinn Féin offices on the Falls Road.

The Press Conference is Important for the Following Reasons:

1. At a delicate point in the peace process Gerry Adams, the President of Sinn Féin and an alleged member of the Provisional IRA Army Council, takes questions from the press. Adams expresses his frustration – "we need to move with some urgency" – and his distrust of the British government – "for the last number of years you have been fed a British government line." And he makes it very clear that the Provisional IRA will not accept the decommissioning precondition, with or without an international commission.

2. Adams responds to Sir Patrick Mayhew's suggestion about an international commission, but he speaks to several different audiences. The Provisional IRA leadership viewed the unilateral ceasefire as a tactical maneuver that would be ended if it did not yield results in a reasonable amount of time. If the peace process failed, the credibility of Gerry Adams – and the credibility of Martin McGuinness and their key advisors – would suffer a terrible blow.16 By holding the press conference outside of Sinn Féin's West Belfast offices, and by repeatedly stating that decommissioning was a "non-starter," Adams was reassuring his militant base. At the same time, because he genuinely wanted to end the conflict in Northern Ireland, Adams had to insist that Sinn Féin be included in the peace process. By emphasizing that Sinn Féin was a political party "which doesn't have weapons" and that "we are committed to moving ahead," he was reaching out to the establishment, especially the British and Dublin governments.

3. Gerry Adams' call for the British government to bring "about a negotiated peace settlement" demonstrates how far the Provisional IRA and Sinn Féin had moved in their demands. The Provisional IRA was created in December of 1969 and "Provisional" Sinn Féin was created in January of 1970, and at the leadership level there was overlapping membership. The initial leadership called for a British declaration of intent to withdraw from Ireland along with a specific date by which a planned and orderly withdrawal would be completed. In the late1970s, when younger people, including Adams and Martin McGuinness, moved into the leadership of the Provisional IRA and Sinn Féin, their demands were more hardline. At the 1980 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis, for example, Jim Gibney put forward a motion calling for "the immediate and total withdrawal of British troops from Ireland."17 The motion was passed. At the 1986 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis, Martin McGuinness promised the delegates,

"Our position is clear and it will never, never, never change. The war against British rule must continue until freedom is achieved."

That hardline approach softened over a relatively short period of time. In his keynote address at Bodenstown in 1992, Jim Gibney stated,

"after a quarter of a century of unbroken resistance to the British occupation of the Six Counties…there is a different world to the one that existed in the mid ‘60s….We know and accept that the British government's departure must be preceded by a sustained period of peace and will arise out of negotiations"(emphasis added).18

Three years later, during the July 25 press conference, Gerry Adams did not call for a British withdrawal from Ireland but instead called for a "conclusive dialogue without preconditions of all the parties in conflict becoming all parties in a solution."

4. Adams' demand for an inclusive settlement – "inclusive dialog without preconditions," "all-party talks," "all-party dialog and a negotiated settlement" – was critical to the success of the peace process. Demanding "all-party" dialog minimized the possibility of "spoilers" and supported Sinn Féin's demand for rights and access to political power. By acknowledging that none "of the other armed groups in this situation" were likely to decommission weapons, he was being even-handed with respect to Loyalist paramilitaries. The objective was to remove "all of the weapons permanently," which would include the weapons of the security forces. Underlying this approach was the possibility that it would provide a pathway to Irish unity through peaceful means.19

5. Adams' comments foreshadow what transpired. The impasse was not resolved and on February 9, 1996, the Provisional IRA ended its ceasefire with a major bomb attack at Canary Wharf, London.20 It was not until Sinn Féin's successes in the 1997 Northern Ireland and Dáil elections, and the British Labour Party's landslide victory in the 1997 Westminster election, that there was substantial progress in the peace process. In the summer of 1997, the Provisional IRA returned to ceasefire but did not decommission weapons. Soon after this, Sinn Féin was admitted to all-party peace negotiations. With the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement (April 1998), Sinn Féin agreed to a negotiated settlement that did not include a British declaration of intent to withdraw from Northern Ireland, and the Provisional IRA still had not decommissioned its weapons.21

(New York, September 1997)

Summary

The Irish peace process transformed conflict–ridden Northern Ireland into a society that tries to resolve political differences through non-violent and constitutional means.22 Gerry Adams' press conference in July 1995 is one of many events that contributed to peace. His comments reflect many of the dynamic political forces that were involved in the transition from political violence to peaceful politics.

1Marisa McGlinchey, Dieter Reinisch and Tim White offered valuable comments. They are not, however, responsible any for errors of fact or misinterpretation.

2Photo credits: "1995 Easter Commemoration, Carrickmore, County Tyrone," and "Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness (New York, September 1997)," courtesy of The Irish People Collection at the IUPUI University Library; "1996 Graffiti in Derry (August 1996)," courtesy of The Irish Republican Movement Collection at the IUPUI University Library.

3The full text of the Provisional IRA statement may be found here: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/ira31894.htm, accessed May 3, 2022.

4Different authors provide different start dates for the conflict in Northern Ireland and for the start of the peace process. An alternative start date for the conflict, for example, is October 5, 1968, when a civil rights march was attacked by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Similarly, the start of the peace process may be dated from the early 1980s and efforts by Gerry Adams to reach out to various parties, including the Dublin government, or the Duisburg Talks in 1988 which brought together constitutional politicians (e.g., Ed Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA (London: Penguin, 2007).

5The "Joint Declaration for Peace" may be found here: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/dsd151293.htm, accessed May 3, 2022.

6The Combined Loyalist Military Command statement may be found here: (https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/clmc131094.htm, accessed May 3, 2022).

7George Mitchell, Making Peace (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), p. 25.

8"Peaceful Demonstrations Attacked by RUC," The Irish People (May 13, 1995, p. 1 (https://iuidigital.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/IP/id/16864/rec/20, accessed April 29, 2022).

9CAIN Web Service, June 20, 1995: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch95.htm (accessed April 29, 2022).

10It was initially reported that the meeting only included Gerry Adams and Sir Patrick Mayhew. It was later revealed that there had also been an earlier meeting (see CAIN Archive, Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland, "Wednesday, 24 May 1995," https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch95.htm, accessed April 29, 2022).

11"Adams, Mayhew Hold Secret Talks," Christy Mac an Bhaird, The Irish People, July 29, 1995, p. 1 (https://iuidigital.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/IP/id/17059/rec/31, accessed April 29, 2022).

12"RUC brutality at City Hall protest," Pádraig Ó Muirigh, The Irish People Vol 24/31 (August 5, 1995), p. 3.

13"All-party talks call at Leinster Rally," An Phoblacht/Republican News, July 27, 1995, p. 2.

14Alexander MacLeod, "Hush-Hush Huddle Pushes N. Ireland Closer to Peace," The Christian Science Monitor, July 24, 1995.

15Gerry Adams, "British may be miscalculating IRA position," An Phoblacht/Republican News, July 27, p. 7; Gerry Adams, "British may be miscalculating IRA’s position," The Irish People Vol. 24/31 (August 5, 1995), p. 5 (https://iuidigital.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/IP/id/17032/rec/32, accessed April 27, 2022).

16Ed Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA, pp. 401-408, 422-441.

17"A Serious Debate – Overshadowed by H-Block Hunger-Strike," An Phoblacht/Republican News, November 8, 1980. For the Provisional IRA and Sinn Féin demands in the 1970s, see Thomas Hennessey’s insightful, The First Northern Ireland Peace Process: Power-Sharing, Sunningdale, and the IRA Ceasefires 1972-76 (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, esp. pp. 148-233) or Robert White, Out of the Ashes: An Oral History of Provisional Irish Republicans (Newbridge, Co. Kildare, 2017, pp. 118-137). See also Niall Ó Dochartaigh, Deniable Contact: Back-Channel Negotiations in Northern Ireland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

18"Bodenstown Speech by Sinn Féin’s Jim Gibney," (https://www.sinnfein.ie/contents/15179, accessed April 26, 2022). Gibney also referred to the Sinn Féin policy document, "Towards a Lasting Peace," which was distributed at the 1992 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis and states, "there is an onus on those who proclaim that the armed struggle is counter-productive to advance a credible alternative," which was an indication that the Provisional IRA was looking for help in ending its armed struggle.

19See Timothy White (editor), Lessons from the Northern Ireland Peace Process (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014).

20The Canary Wharf bomb killed two people and caused an estimated £150 million in damage.

21The full text of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement is available here: https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/agreement.htm (accessed April 29, 2022). In 2005, the Provisional IRA finally completed the decommissioning of its weapons.

22The political history of Northern Ireland post-1998 is complex, the peace process has not always been smooth, and there remain a minority of activists who continue to endorse the use of armed struggle to achieve political change. See Marisa McGlinchey, Unfinished Business: The Politics of Dissident Irish Republicans (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2019).